Home | Part 1: Tracing the History | 2. Dutch Factory on Deshima

Part 1: Tracing the History

2. Dutch Factory on Deshima

(1) From Hirado to Nagasaki

However, the Shogunate government was increasingly inclined to restrict the entry of Westerners into Japan. Christianity had already been banned by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in 1587 and the missionaries expelled, but the Shogunate government further tightened the ban on Christianity, and in 1635 prohibited Japanese from going overseas and those who sailed overseas from returning to Japan. Great Britain lost the competition with the Netherlands and had already closed its factory in 1624 and left Japan. In that same year Japan broke off relations with Spain. In 1636, the Portuguese were segregated to the man-made island called Deshima built in Nagasaki and were subsequently expelled from Japan in 1639 and prohibited from returning. The Protestant Dutch promised not to proselytize and were given permission to continue trading, but in 1640 the factory in Hirado was ordered destroyed. The direct pretense was because a Christian era date marking the date of construction was written on a warehouse. At the time, the chief of the Dutch factory F. Caron (II-1) followed the order without resistance. In May of the following year, the Dutch factory was ordered moved to Deshima, which had been vacated by the Portuguese.

(2) Dutch Factory and Trading at Deshima

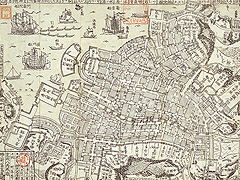

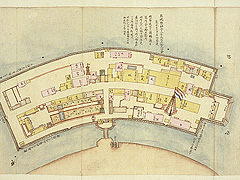

Thereafter, the Dutch factory employees were crowded onto Deshima, which was connected to the mainland by one stone bridge and covered an area of only about 15,000 square meters, and were much more strictly monitored than before.

There were about 60 structures on the island as well as a vegetable garden and other features. The Japanese called the chief of the Dutch factory "kapitan" and the deputy "hetoru," and including these the island was occupied by about 10 to 15 Dutchmen, including a secretary and other factory employees, physicians, carpenters, cooks, and others, and Javanese who were brought as servants. In addition, many interpreters and others worked there. The Dutchmen were not allowed to freely leave the island and visits to the island by Japanese were also severely restricted.

A Dutch ship docked once a year, and the goods that could be traded and their quantity and price, etc. were severely restricted. But since a commensurate profit was assured, the Dutch did not abandon their trading rights even under such restrictive conditions, and chiefs of the Dutch factory were continuously asking for permission to maintain or increase the quantities. The factory employees were also allowed to engage in personal trade of specific items (called wakini trade). Some goods were also secretly brought in and sold, so being assigned to Deshima could yield significant extra income.

The main imported goods were Chinese raw silk, silk fabric, sugar, scented wood, pepper, shark skin, and medicines (II-4) , while the main exported goods were initially silver (export forbidden after 1668) and gold (mostly in the form of oval coins; export prohibited in 1763), and later copper (copper bars), but craftwork such as ceramics and lacquerware were also exported. The processed copper bars, which were mostly refined in Osaka, were the most important export good, and the usual practice was for the Dutch to tour the Osaka refineries on their way back from their trip to appear in court in Edo.

The way trade was conducted changed with the times, but it was all handled by the Nagasaki accounting office from 1698. Imported goods were purchased in bulk by the accounting office and transferred to merchants. The transaction price was unilaterally set by the Japanese government. Export goods of comparable value were given to the Dutch. This managed trade system continued until the end of the Shogunate government.

The interpretation and document translation between Japanese and Dutch were done by hereditary Dutch interpreters (approximately 30 or more families). The interpreters were ranked, such as senior interpreter and junior interpreter, which were further divided into more specific classifications. Their original duty was trade negotiations, but some received academic training in medicine, physics, and other fields and then instructed Japanese students, read Dutch books, or worked as document and book translators. Former interpreters such as Motoki Ryoei, Shizuki Tadao, Yoshio Kogyu, and Baba Sajuro are noted for their deeds. The Dutch interpreters were the hidden force behind the Western learning boom. (II-2)

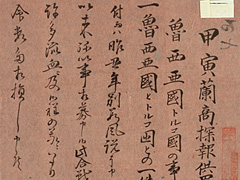

(3) Submission of Fusetsu gaki (News Reports) and Court Journey

The Shogunate government severely restricted and monopolized foreign trade and the inflow of information from outside Japan. For this reason, a report of foreign events was required when a Dutch ship made port. The submitted information was translated into Japanese by an interpreter and sent to Edo. This was called Oranda fusetsu gaki (Dutch News Reports). Originally, the main purpose was to obtain information on the actions of enemy European countries, such as Portugal, and to prevent the infiltration of missionaries. The Dutch actively worked to provide this information as a show of loyalty for being allowed to continue trading. This information was monopolized by a few individuals, such as the top leaders of the Shogunate government and the Nagasaki Magistrate, but information did leak out from related persons and by the end of the Edo period much information was copied and distributed.

As mentioned above, in appreciation for permission to trade and to continue trading, chiefs of the Dutch factory were required to travel in entourage to Edo to appear before the Shogun and present him with gifts. At first, this audience was required once a year, but later was reduced to once every 4 years and was conducted a total of 166 times. During the late Edo period, the entourage was very large and included the required chief of the Dutch factory, his secretary and physician, and many accompanying Japanese. This was the only opportunity for a Dutchman to view Japan from the inside and was also a rare opportunity for the Japanese in Edo and along the entourage route to see a Westerner. During the court journey to Edo there was interaction with Japanese and there were many chiefs of the Dutch factory and physicians who contributed to Japan studies (II-1). In addition, there were also Dutch studies scholars and feudal lords interested the West who visited the Nagasakiya in Edo, the designated place of lodging for the chief of the Dutch factory and his entourage, to ask many questions.

-

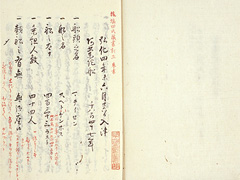

Record of the dialogue between Otsuki Gentaku and a Dutchman on court journey

Seihin taigo. -

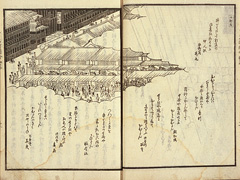

View of Nagasakiya by Hokusai

Ehon azuma asobi. -

Outside view of Nagasakiya by Hiroshige

Kyoka Edo meisho zue. -

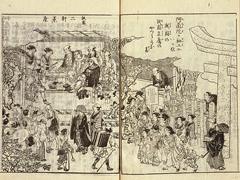

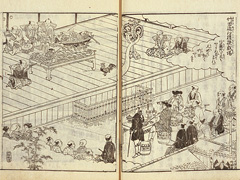

Dutch entourage viewing Gion

Shui Miyako meisho zue. -

Dutch viewing a theatrical performance at Dotonbori

Settsu meisho zue.

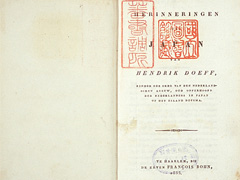

(4) Annexation of the Netherlands by France and the Phaeton Incident

Thereafter, trade between Japan and the Netherlands stagnated, largely due to the political situation in the Netherlands.She was invaded in 1795 by the French Revolutionary Army and came under the control of France as the Batavian Republic. Business also worsened for the VOC, which was dissolved in 1799 (thereafter trade was run by the government). Then in 1806, Louis Bonaparte, the younger brother of Emperor Napoleon, became king of Holland, and in 1810 the country was annexed by France. The colonies were also affected by the wars in Europe, and Batavia, which had lost its naval supremacy to Great Britain who was fighting domination by Napoleon, managed to keep a little trade with Japan going, using such measures as employing the merchant vessels of the United States of America, a neutral country. Batavia, however, was occupied by Great Britain in 1811, disrupting the landing of trading ships in Nagasaki and causing the factory employees at Deshima to suffer for lack of food and clothing. The chief of the factory at the time was H. Doeff (II-3), who skillfully rode out this period and had to carefully avoid mentioning the situation in his home country in News Reports. At this time, it is said Deshima in Nagasaki was the only place in the world flying the flag of the Netherlands.

In the meantime, a ship flying the flag of the Netherlands finally made port at Nagasaki in October 1808, but it was actually the British warship Phaeton. The factory employees that went on board were taken hostage, asked whether there were any Dutch ships in harbor, and demanded food and supplies. Since there had never been similar trouble to this point, the Saga Domain, which was charged with guarding Nagasaki, did not have sufficient military strength, so the Nagasaki Magistrate Matsudaira Yasuhide, on the advice of H. Doeff, had no choice but to give into the demands and allowed the British ship to leave. Soon after authorizing a report to the Shogunate government, Yasuhide took responsibility for giving into the demands and took his own life.

After this incident, the procedure for allowing Dutch ships to make port became very stringent. This also prompted military studies in coastal protection and the learning of the English language by Dutch interpreters. This incident was also one of the reasons behind the Order to Drive Away Foreign Ships issued in 1825.

When the Netherlands become free of French rule in 1813 with the downfall of Napoleon, an effort was made to restore trade with the East, and in 1823 the Batavian government sent the German physician P. F. von Siebold to Japan to gather information on the country. (II-1)

Copyright © 2009 National Diet Library. Japan. All Rights Reserved