- Kaleidoscope of Books

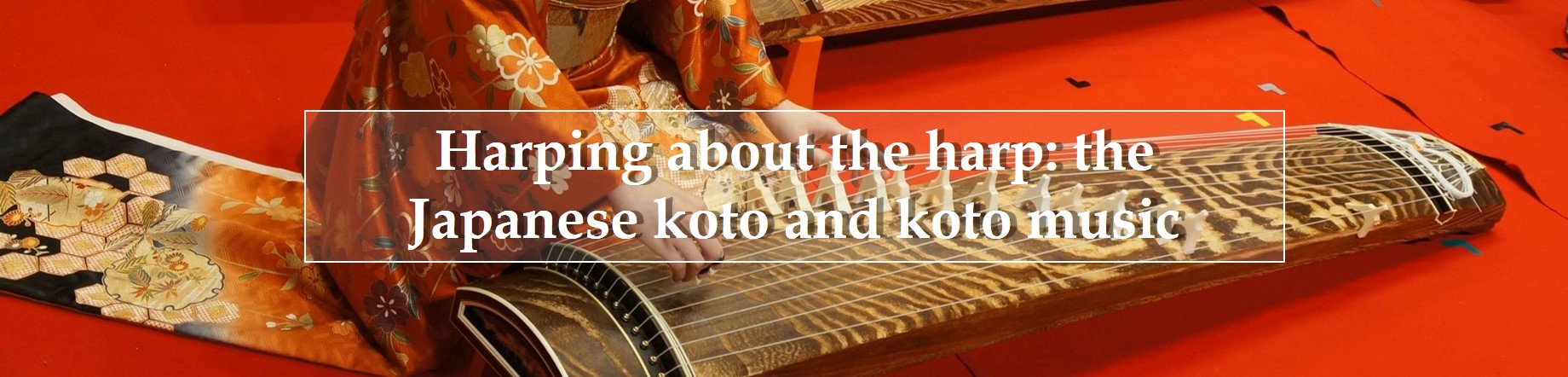

- Harping about the harp: the Japanese koto and koto music

- Chapter 2: Depictions of the koto in pre-modern art

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Koto melodies

- Chapter 2: Depictions of the koto in pre-modern art

- Chapter 3: Artist of koto music

- Afterword/References

- Japanese

Chapter 2: Depictions of the koto in pre-modern art

The koto was brought to Japan in Nara period, around the eighth century, and was used at major events of national interest in ensembles together with instruments such as the biwa, Japanese lute, and fue, Japanese flute. The Gagakuryo was formed in 701 per the provisions of a major reform known as the Taiho Code and served as an imperial agency responsible for both foreign and indigenous forms of music and dance performed at the imperial court.

Although the Gagakuryo itself gradually declined in importance after the Heian period, the forms of music and dance that it dealt had already become popular among courtiers. Not only were these works performed at imperial events, the aristocracy also made the enjoyment of musical instruments a part of daily life.

Depictions of the koto in the diaries of and fiction by Heian period aristocracy

The koto is mentioned in many stories written about the Heian period. The Tale of Genji [WA7-279] contains a scene, in which four nobles perform with an ensemble of instruments including koto to celebrate the fiftieth birthday of retired emperor. In another scene, a noble woman plays the koto to express her love and sorrow, when her lover and protagonist of the story, Hikaru Genji, departs for Kyoto.

With musical performances flourishing at the Imperial Palace, an imperial agency for managing such performers was established. Similar agencies could also be found in Nara and other places where major Shinto and Buddhist rituals were accompanied by the performances. But as court society declined during the late Heian period, so too did the once flourishing need for court music fall off, although some players managed to survive through the patronage of shrines, temples, or samurai families.

During the last half of the 16th century, during the Azuchi-Momoyama period, a priest named Kenjun (ca. 1534–ca. 1623) reorganized the existing forms of koto music for court music and songs, which are preserved at the Zendoji temple in Kyushu’s Kurume region, into what is now recognized as the Tsukushi school of koto music. One of Kenjun’s disciples, Yatsuhashi Kengyou, continued this work, which contributed to the popularization of koto music during the Edo period.

The spread of koto music during in the Edo period

Throughout the Edo period, the composition, performance, and teaching of koto music was generally undertaken by blind males, who organized themselves into a mutual-aid society for professional koto players. And since many of these men were also expert shamisen players, music for these two instruments developed in parallel. Later, as this style of music became more popular, it was expanded to include the kokyu and shakuhachi. And in addition to professional performers, taking koto and shamisen lessons was also a popular diversion for women.

During the Edo period, the citizens would commonly organize seasonal events that included banquets accompanied by music and dancing. In addition to traditional flower-viewing parties, events for viewing the full moon, viewing autumn foliage, catching fireflies, or even digging clams could all be occasions for music. Many publications from this period, such as Naniwa kagami (Naniwa Reflections), edited by Ichimuken Doya [162-91], or Owari meisho zue (Famous Places in Owari), edited by Okada Kei and Noguchi Michinao [839-76], contain images depicting such events as well as historical sites and local topography.

This portrait shows Bando Mitsugoro III and other kabuki actors

playing the koto and shamisen together at a private residence on the night of a moon-viewing party

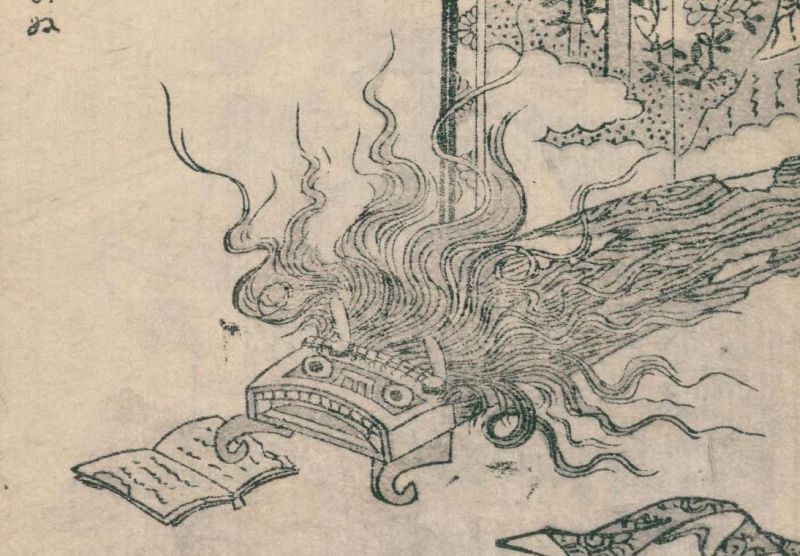

6) Hyakki tsurezurebukuro, illustrated by TORIYAMA Sekien, 1805 [わ-38]

Hyakki tsurezurebukuro, a collection of phantasmagorical illustrations, was one of several books produced by Toriyama Sekien, including Gazu hyakki yagyo (Hyakki yagyo published by Naganoya Kankichi, 1805 [辰- 23]) which is bound with six Hyakki yagyo shui, Konjaku ezu zoku hyakki, and Konjaku hyakki shui. Many of the paintings of this book were derived from Tsurezuregusa [WA7-219] and Hyakkiyagyoemaki [亥-106]. Volumes 1–3 contain illustrations of about 50 different phantasmagorical beings.

Next Chapter 3:

Artist of koto music