![]()

Section 4: Revue and chanson

This section will look at revue and chanson, which developed in a unique way in Japan among the various mass entertainments which was imported from France and became popular.

These 2 forms of entertainment were brought to Japan through the Takarazuka Girl's Revue Mon Paris. Revues instantly became a boom throughout the country, blossoming into girl's revues and kei engeki (light comedy). Popular French songs are called "chanson", and after the war they became a major hit with large numbers of chanson cafés opening, etc. The unique development of these entertainments, might be seen as strange from their place of origin, however their mark on the history of Japanese popular entertainment is notable.

In addition, a characteristic of both is their emphasis on specific images of France (particularly Paris). Romantic/erotic? Common/intellectual? For the Japanese, the touch of France can be seen here.

The 1920 Paris Revue

First let's look at the French Revues of the time which were imported through Mon Paris. In France at the time, there was a culture of having music, acrobatics, dance, skits and other entertainment at facilities called cafe concerts and music halls (similar to music halls or night clubs where food and drink are also served in Japan). At particularly large music halls revues were performed. Revues were a series of acts which could include a combination of music, dance, skits, etc., where the scenes progressed rapidly with showy costumes and fixtures and lighting, altogether making for a spectacle to be enjoyed. The apex of these forms of entertainment was the 1920's, when performers including Mistinguett (?-1956) and Josephine Baker (1906-1975) performed at music halls including Casino de Paris, Folies Bergere and the Moulin Rouge.

Moulin Rouge music-hall: M. Pierre Foucret présente: La Revue Mistinguett, Paris: Central Publicité, [1925] [VA251-402]

Held in the Ashihara Collection. This is a performance pamphlet for a revue starring Mistinguett at the Moulin Rouge. It is 32 pages in B5 size. The cover features a number of posters of Mistinguett's performances, and was done by Charles Gesmar (C1900-1928), who also designed costumes. The main text notes the performers and staff for each scene. "November 1925-July 1926" is written in pencil. Mistinguett was characterized by a gravelly voice and a big-sisterly disposition, and the beauty of her leg lines was one of her major selling points, and it is said it was a spectacle to behold to see her come down the large stairs on the stage with a set of giant wings on her back.

Mon Paris - Paris, nostalgic even on a first trip

The Takarazuka Girl's Revue was established as an attraction at a hot spring resort area as the Takarazuka Chorus Groupe and became popular, however in 1924 the construction of a huge theater that could seat 4000 people led to a standstill with the existing performances which consisted of adaptations of fairy tales and kabuki plays, so director KISHIDA Tatsuya (1892-1944), originally from the Opera section of the Imperial Theater and the Asakusa Opera, was sent to Europe and America. KISHIDA was the 5th son of KISHIDA Ginko (1833-1905), and the younger brother of Ryusei (1891-1929). Mon Paris (My Paris) was announced in September of 1927 as the result of his travels overseas.

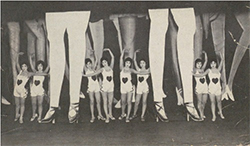

The main character KUSHIDA departs from Kobe Port and travels to various countries around the world before arriving in Paris, basically adopting KISHIDA'S own travel. The finale is set in a music hall play within a play set in the Palace of Versailles. Songs and dances directly imported from Paris are liberally placed throughout the performance, the performance was very speedy, with no curtain drops, featured the first line dance in Japan and introduced a new trend in entertainment to a then "modern" generation. The show was a huge hit, to the degree that it is said that even people walking around the town in Tokyo could be head singing the theme song Mon Paris.

The original music for the theme song was Vincent Scotto's (1874-1952) composition Mon Paris, and the song is nostalgic about the Paris of old, stating, "My Paris, with no subway and no buses, was so beautiful", with a lighthearted rhythm and pleasant tone. This would be the first popular French song to have come to Japan. In KISHIDA's translated lyrics, it is distinctive that a simple traveler refers to Paris as "My". At this point in time, FUJITA Tsuguharu (1886-1968) and other artists living in Paris were well known, and Paris was already a city of infatuation. Having Paris recreated up on the stage with the lyric "My Paris" being hummed (there is a scene during the play where the audience in instructed on how to sing the song), likely gave the audience the feeling that Paris was their own town and made them happy.

In addition the performance poster was a complete imitation of Gesmar 's performance poster starring Mistinguett.

Takarazuka shōjo kagekidan (Ed.), Takarazuka shōjo kageki 20nenshi, Takarazuka shōjo kagekidan,1933 [650-13] ![]()

Mon Paris stage photo printed in the "The age of revue is coming" item.

Tōkyō ongaku shoin henshubu (Ed.), Aishō kashū 2, Tōkyō ongaku shoin, 1933 [特270-220]

A book that presents melody scores of various Japanese and Western songs. Mon Paris is the 3rd song, following Pari Sai (lit. Paris Day) and Under the Roofs of Paris.

Girl's Revue: Paris, pure and romantic

Under KISHIDA's apprentice SHIRAI Tetsuzo (1900-1983), the revue which KISHIDA had created further bloomed.

In Parisette, the 1st work he produced in 1930 after his travels abroad, not only were the clothing and makeup made to be more similar to those actually used in Paris, but light pink and light blue were emphasized as the colors of Paris. In addition, Sumire no Hanasaku Koro, which would become theme song for the Takarazuka, was song, however the lyrics to the original on which it was based, Wenn der weiße Flieder wieder blüht (When the White Lilacs Bloom) were about seasonal things, but SHIRAI changed this to sumire (pansies), and made it a nostalgic first love song. In addition, the main character falls in love with a Parisienne, making Paris feel closer. In his later work, SHIRAI changed the song Oui Je suis de paris (I am a Daughter of Paris) to Hanazono Takarazuka (Takarazuka Flower Garden) (1937 performance Takarasienne), and continued to work to promote the idea that "Paris=Takarazuka=utopia".

Thereafter in the Takarazuka Girl's Revue, Paris was depicted as a pastel-colored, romantic utopia. This image was following in other girl's revues.

Akadama shōjo kagekidan (Ed.), Mūran rūju kānivaru: Akadama shōjo kageki tokubetsu kōen, Akadama shōjo kagekidan, 1935 [特252-902]

With the popularity of the Takarazuka Girl's Revue, a number of other girl's revue companies sprung up around the country, including the Shochiku Opera Troupe, however after Mon Paris, all of these companies also began to incorporate revues. The Akadama Girl's Revue was established in 1927 and was presided over by the Osaka Dotonbori cabaret Akadama. The revue imitated the Takarazuka Girl's Revue and used a school system. This is a photo album from the performance Moulin Rouge Carnival. According to the included summary, the work is a perfect fantasy story wherein a Japanese girl Momiji (lit. red leaves) studies abroad in Paris, falls in love with the young painter Fritz, and has her debut at the Moulin Rouge, but she must return to Japan due to her father's death however Fritz follows her, making for a happy ending. The "forced separation followed by a grand finale" was a pattern also often seen in SHIRAI's works.

Sham revues: Paris, ero guro nansensu (erotic, grotesque, and nonsense)

Although girl's revue claimed to be direct imports, there were elements which were completely eliminated. Namely, erotic elements. In the originals, there were often scenes where the dancing girls would be naked from the waist up. The so-called "sham revues" imported this facet of the originals. In terms of scale, these shame revues could not match the actual revues, which lead to the use of the self-appointed name "sham", however the very sham nature of the reviews, their eroticism and humor proved popular, and they thrived as Kei engeki (light comedy), which were perfectly suited to the erotic, grotesque, nonsense social trends of the time. In addition, the skit and play elements which accompanied (or where included in) the revues, were succeeded by later plays, movies and television.

(1) Casino Folies

The first permanently established sham revue was the Casino Folies established in Asakusa in July 1929. The plan was to establish it in the Hakusan area Nantendo bookstore and restaurant, which was famous as a gathering spot for Dadaist and anarchists. The name was, of course, a combination of the Casino de Paris and Folies Bergere. The revue also made an appearance in the newspaper serialized story Asakusa Kurenaidan [603-242] by KAWABATA Yasunari (1899-1972) which began in December of the same year, and a rumor that the dancing girls would drop their pants on Fridays made the revue hugely popular. It is well-known that comedy actor Enoken (ENOMOTO Ken'ichi, 1904-1970) started here. A number of other revues, both large and small, continued to flood Asakusa thereafter.

Kajinofōrī bungeibu (Ed.), Kajinofōrī revyū kyakuhonshū, Naigaisha, 1931 [603-362]

(2) Moulin Rouge Shinjukuza Theater

The Moulin Rouge Shinjukuza Theater was started in Shinjuku in December of 1931. The theater imitated the original theater of the same name in Paris, and the red electrical windmill attached to the building was its landmark. Tokyo expanded to the west after the Tokyo Earthquake of 1923, and Shinjuku flourished as a suburban terminal station. The Moulin Rouge targeted the new middle class which lived in the suburbs and used its amateurishness as its selling point, and the lively review with its teenaged dancing girls was very popular. It is estimated that the plays lead to the post-war home dramas (TV dramas of family life).

Asahi shinbun, 1933.10.10, Evening paper, p.2 [Z81-1]

Advertisement of the 64th performance. Higeo Mamoru no Hige (Higeo Mamoru's Mustache) was a nonsense play about a mustache which leaves its owner and attaches itself to a variety of people, hinting at Gogol's The Nose.

Chanson: Paris, the city that sings about life

(1) Prewar period

Mon Paris was presented in 1927. Thereafter, TAYA Rikizo (1899-1988) sang theme song for the 1931 talkie film Under the Roofs of Paris, however the word "chanson" was not yet in common use at this time.

The name "chanson" is said to have begun being used for the record of Lucienne Boyer's (1901-1983) Parlez-moi d’amour (Speak to Me of Love) which was released in 1932. This brought the singing voice of the original singer to Japan. Thereafter chanson spread through imported records and AWAYA Noriko (1907-1999) and others who sang them with Japanese lyrics. Because chanson had a refined image, popular songs of the time began to have titles such as "Biwako Chanson (Lake Biwa Chanson)", to try and share in the popularity of chanson.

Columbia Society of Music Connoisseurs (Ed.), Shanson do Pari kaisetsusho, Nihon chikuonki shōkai, 1940.5 [KD841-H350]

The peak of chanson in the prewar period was the 6 SP set Chanson de Pari (Chanson of Paris) which was sold by Japan Columbia in 1938. This work was luxurious, featuring audio sources from Paris together with added explanations, and cover and illustrations by FUJITA Tsuguharu. At a time when 1 record cost 1 yen 50 sen, this was an expensive 11 yen, however it was extremely popular and 12,000 copies sold, exceeding the originally planned 2,000 copies. ASHIHARA Eiryo (1907-1981) edited and provided the explanations, and was very interested in French culture including chanson, as a result of the influence of her uncle FUJITA, and had many achievements as an introducer of French culture.

This text is the booklet from the 2nd volume (sold in 1940) of this popular record collection. This also sold 12,000 copies. The cover Western-style painting is by MIYAMOTO Saburo (1905-1974). MIYAMOTO travelled to France from 1938 until the following year. In "Paris chanson" ASHIHARA explains, "The general public are not just listeners, they are the ones who sing" and "it is more correct to say this is a drama, rather than a song".

(2) Postwar period

From around the late 1940's, chanson boom occurred on an enormous scale. There were a number of major happenings related to chanson including the opening of the chanson café Ginpari (Paris d'argent) (1951), the visit to Japan by popular singles Damia (1889-1978) and Yvett Giraud (1916-2014), Yves Montand's (1921-1991) Autumn Leaves, etc. becoming a hit. Japanese singers were very successful, and a large number of chanson produced by Japanese also appeared. Record appreciation circles were also held in various areas. Even being introduced in magazines aimed at junior high school students stating, "they do not simply string together pretty words, but speak about something basic about life", "songs which everyone can enjoy singing, from tradesmen to ministers", and "France's chanson are songs which permeate tree lined roads and stone walkways" (Chugakusei no Tomo 2 Nen (The Junior High School Student's Friend 2nd year) 4(10) 1961January [Z32-465]).

In France, chanson refers to songs in a broad sense. However for the Japanese, "chanson" are songs that fit the above type of images which were established during these times.

Tōchiku shanson tomo no kai sōritsu kinen shanson konsāto Nagano toshokan hōru kaisetsu: Ashihara Eiryō, [19--] [VA331-30]

Held in the Ashihara Collection.