![]()

Section 1: Cuisine

France is, above all else, a country of great food. This gastronomy is well known through works such as Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin's (1755-1826) Physiology of Taste. The Western cuisine which was introduced after the opening of Japan was a mix of French, German, British and other cuisines which became popular as "yoshoku (lit. Western dishes)", however it was French cuisine in particular which was served at diplomatic, imperial court and other official functions. This section will trace the history of French cuisine in Japan through records of the cooks, books on food published in Japan and other sources.

The origin of “yoshoku”

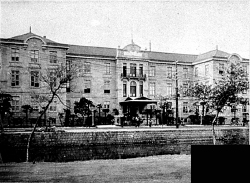

In 1868, the Restoration government established a foreign settlement in Tsukiji for the opening of Tokyo. Facilities aimed at the foreigners were also established in the settlement, including restaurants which served Western food. The person employed as the head chef at the Tsukiji Hotel, the first Western style hotel in Japan which was opened that same year, was a Frenchman, Louis Begeux (birth and death dates unknown). The hotel building was lost in a serious fire in 1872; however Begeux remained in Japan thereafter and also worked as the head chef at the Yokohama Grand Hotel. In 1887, he became the owner of the Kobe Oriental Hotel which he developed into the leading hotel in Asia. British author Joseph Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936) came to Japan in 1889 and in a letter (contained in Rudyard Kipling, From sea to sea, and other sketches; letters of travel [衆9660-0003]) he wrote, "Excellent Monsieur and Madame Begeux!", praising the hotel's food as well as the service provided by the Japanese staff. Begeux also had a hand in preparing meals for banquets at the Imperial Palace and became the "father of French cuisine" in Japan.

Ichiyōsai Kuniteru, Tōkyō Tsukiji Hoterukan han’ei no zu, Daikokuya Heikichi, [1868] [寄別7-4-2-5] ![]()

A nishiki-e (brocade picture) depicting the Tsukiji Hotel. The plastered walls were an iconic feature of the semi-Western building.

The Taisei Kunmō Zukai [特42-506] issued by the Ministry of Education in 1871 included images of Western cultural items, and among its contents one can find "plate and glass", "kitchen utensils" and "cellar". It is very interesting that these types of items were introduced well before the average person ever had a chance to try yoshoku. There were also two works published on cooking methods and recipes as early as 1872, KANAGAKI Robun's Seiyō Ryōritsū [特41-857] and Keigakudo Shujin's Seiyō Ryōri Shinan [特54-156]. It should be noted that both works are written for the purposes of leading to national development by strengthening the bodies of the Japanese using nutritional western cuisine based rational preparation methods. Before Seiyō Ryōritsū, KANAGAKI Robun (1829-1894) also wrote the comic story Aguranabe [245-9] ![]() of commoners in the enlightenment period set in a sukiyaki restaurant.

of commoners in the enlightenment period set in a sukiyaki restaurant.

TANAKA Yoshio and UCHIDA Shinsai (Tr.), Taisei kunmō zukai, Monbushō, 1872 [特42-506] ![]()

An illustration of western cultural items with parallel translations in German, English, French and Japanese. A Western kitchen and cookery are depicted.

Robun (Ed.), Kyōsai (Draw), Seiyō ryōritsū, Mankyūkaku, [1872] [特41-857] ![]()

Keigakudō shujin, Seiyō ryōri shinan, Karigane shooku, 1872 [特54-156] ![]()

Tsukiji Seiyoken and yoshoku culture

In addition to the above hotel, other restaurants which served yoshoku also began to appear in Tsukiji, which had become a foreign settlement. KITAMURA Shigetake (1819-1906), who served IWAKURA Tomomi (1825-1883), was sad at the lack of facilities for entertaining foreign workers, and on April 3, 1872, founded Tsukiji Seiyoken. However, Seiyoken was completely destroyed on that day in the major fire that occurred in Ginza (this was also the fire that destroyed the Tsukiji Hotel). KITAMURA rebuilt Seiyoken the following year, and opened a branch in Ueno in 1876. Seiyoken could be said to have been the first real Western style restaurant in Japan and was the center of yoshoku culture during the Meiji Era. Ueno Seiyoken was close to Tokyo Imperial University and was loved by scholars and literati, even being mentioned in NATSUME Soseki's (1867-1916) Sanshirō.

Known cooks at Seiyoken include 4th head chef NISHIO Masukichi (1846-?) and 5th head chef SUZUMOTO Toshio (1890-1967). After joining Tsukiji Seiyoken, NISHIO travelled to France and had the opportunity to work at the Paris Ritz Hotel. Georges Auguste Escoffier (1846-1935), the author of Le Guide Culinaire who was known as the "father of French cuisine", worked at the Ritz at the time. After returning to Japan, NISHIO became the head chef and led Seiyoken to its highest period of prosperity. SUZUMOTO, who took over after NISHIO, worked as the head chef at the Kobe Oriental Hotel opened by Begeux, then joined Tsukiji Seiyoken. He was called "the master" and wrote a manual for cooks based on Escoffier’s book.

Seiyōken shujin, HATTORI Kunitarō (Ed.), Seiyō ryōri kuriya no tomo, Ōkura bunten, 1902 [96-37] ![]()

A recipe book aimed at home use written under the name of the owner of the Seiyoken.

SUZUMOTO Toshio, Furansu ryōri kondatesho oyobi chōrihō kaisetsu, Keibundō shuppanbu, 1920 [395-13] ![]()

A manual by SUZUMOTO. It is designed so that it can be kept in a pocket and carried around.

Rokumeikan and WATANABE Kamakichi

The revision of the unequal treaties concluded during the last days of the Tokugawa shogunate was an ambition of the Meiji government, and foreign minister INOUE Kaoru (1835-1915) promoted a Europeanism policy to appeal to Japan's civilizing. The introduction of Western cuisine was one of the results of this policy. Already, soon after the Restoration, French cuisine was served for dinners for the Emperor's Birthday, court dinners to which diplomats from various countries were invited and other formal meals, however when the Rokumeikan (lit. Deer Cry Pavilion) was established in 1883 in order to entertain foreigners, French cuisine was served for the dinners (Rokumeikan Dinner Menu (1884) Held by the Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan ![]() ). It became necessary for government officials and military personnel to become familiar with Western manners, and meals at the Tsukiji Seiyoken were recommended for those in the navy in particular. It is said that officers who spent little at the Seiyoken were cautioned at the end of the month.

). It became necessary for government officials and military personnel to become familiar with Western manners, and meals at the Tsukiji Seiyoken were recommended for those in the navy in particular. It is said that officers who spent little at the Seiyoken were cautioned at the end of the month.

WATANABE Kamakichi (1858-1922) was a chef who was apprenticed at the British Legation, Japan. WATANABE's skill was noticed by Alexander Georg Gustav von Siebold, who was active in diplomatic affairs during the last days of the Tokugawa shogunate and during the Meiji Era and was also the son of physician Philipp Franz Balthasar von Siebold (1796-1866) who visited Japan in the Edo Era, and was recommended to the head chef when the Rokumeikan was opened. At this time he recommended his younger brother-in-law and gave him his support, but when the Rokumeikan was moved under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Imperial Household in 1890 (and then later transferred to the Peerage Hall), he was hired as the head chef. Thereafter, in 1907 with the support of MATSUKATA Masayoshi (1835-1924) and KATSURA Taro (1847-1913), IWASAKI Yanosuke (1851-1908) of Mitsubishi Conglomerates became a patron, and he opened the Chuotei (lit. Central Bower) in the Marunouchi Mitsubishi No. 8 Building. It is said the name of the restaurant was based on the Tokyo Central Depot (called "Chuoteishajo" in Japanese, the present day Tokyo Station). From 1903, he taught western cooking methods at Japan Women's University, which was the first modern women's higher education institution in Japan. WATANABE himself was not fortunate enough to have the opportunity to travel abroad lifelong, however it seems that he was able to learn about the West through a relation with UNO Yataro (1858-1929), who was working as the house cook of KOMURA Jutaro (1855-1911), who achieved the revision of the unequal treaties, and other means.

OKADA Kuramatsu, YOSHIDA Yōsaku (Review), Wayō enkai no sahō oyobi sono kinmotsu, Shoheidō, 1912 [特64-846] ![]()

A manual on Western banquet manners. The editor YOSHIDA Yosaku (1851-1927) was a diplomat who worked at the Yokosuka Ironworks and studied abroad in France. He was also the head of the Rokumeikan.

UNO Yatarō, Seiyō ryōrihō taizen, Ōkura shoten, 1926 [342-87イ] ![]()

This is said to be a joint work by UNO and WATANABE. UNO established the first western cooking school in Japan.

The French cuisine of the Imperial Hotel

YOSHIKAWA Kanekichi (1853-1935) studied under the Yokohama Grand Hotel's Begeux, and then worked at the Rokumeikan (lit. Deer Cry Pavilion) before becoming the first head chef of the Imperial Hotel when it was opened in 1890. The hotel was proposed by INOUE Kaoru as a lodging facility for state visitors and founded by SHIBUSAWA Eiichi (1840-1931), OKURA Kihachiro and others, and ruled the Japanese hotel world, accommodating a large number guests over its time. A number of leading Japanese chefs have come from the ranks of the past head chefs of the hotel, with the 11th head chef MURAKAMI Nobuo (1921-2005) in particular being well known as an instructor on NHK TV's Kyo no Ryori (lit. Dish of the day), the head chef for the athletes at the Tokyo Olympics and as the creator of the "Viking" style (all-you-can-eat buffet) inspired by the northern European smörgåsbord appetizer style. He had a friendly rivalry with ONO Masakichi (1918-1997), the head chef of the Hotel Okura from the same generation. In 1971, they played central roles in the establishment of the Association of Disciples of Auguste Escoffier Japan, which was dedicated to introducing legitimate French cuisine.

MURAI Gensai, Kuidōraku, Hōchisha, 1903 [116-255] ![]()

This is a cooking novel by MURAI Gensai (1863-1927). When it was serialized in the Hōchi Shinbun newspaper in 1903, it proved popular and became a best seller when published as a stand-alone edition. He could be said to be the originator of today's gourmet content, but did not only pursue gourmet food, but also had a civilizing, explaining that "not knowing how to prepare food was a negative for domestic budgets", and providing notes for each section as well as nutritional values for food, etc. The frontispiece of the volume of autumn features an image of the Emperor's Birthday banquet held at the Imperial Hotel on November 3, 1903.

ŌHASHI Matatarō (Ed.), Seiyō ryōrihō, Hakubunkan, 1896 [45-184] ![]()

One of the volumes of the Hakubunkan's Daily Encyclopedia. Includes a foreword under the name and title "Imperial Hotel Head Chef YOSHIKAWA Kanekichi".

AKIYAMA Tokuzo, Master Chef to the Emperor

AKIYAMA Tokuzo (1888-1974) trained at the Peerage Hall and Tsukiji Seiyoken when he was young, travelled to Germany in 1909, moved to France the following year, and worked at the Magestic Hotel and Café de Paris. Even after the Russo-Japanese War, at the time there was still remaining prejudice against Asians in Europe, and he was often involved in fights in the kitchen. He managed to get through these fights using judo, and these types of situations were often experienced by Japanese who travelled to Europe at the time. Afterward, he also worked for half a year at the Ritz Hotel under Escoffier. He returned to Japan at the invitation of the Ministry of Imperial Household in 1913, in order to entertain the guests from various countries at Emperor Taisho's coronation ceremony, and was appointed the Master Chef of the Imperial Court the same year at just 25 years of age. His superior at this time was FUKUBA Hayato (1856-1921), Director of the Imperial Cuisine known as a horticulture pioneer in selective breeding of fruit. Thereafter, he worked in the Taisho and Showa Courts for over half a century until retiring at age 84 in 1972. During this time he entertained countless foreign leaders and guests, and his life was written about in a novel (SUGIMORI Hisahide's Master Chef to the Emperor [KH566-199]) and adapted into a television drama. AKIYAMA succeeded Escoffier's line and the lineage of French cuisine in Japan after WATANABE Kamakichi, and the scale of his activities and effect on later generations makes him truly a giant who is fundamental to any discussion of French cuisine in Japan.

AKIYAMA Tokuzō, Furansu ryōri zensho, Akiyama hensanjo shuppanbu, 1923 [507-132] ![]()

In 1920, AKIYAMA was ordered to travel to various countries in America and Europe. Part way through his trip he was ordered to accompany the Crown Prince (later to become Emperor Showa, 1901-1989) on his visit to various countries in Europe, and experienced the court food of various countries first hand. He published this book after returning to Japan. It is a major work, consisting of over 1600 pages, making him worth of the name "the Japanese Escoffier".

Nihon shichūshi kyōdōkai (Ed.), Hyōjun Furansu ryōri zensho, Nihon shichūshi kyōdōkai, 1941 [特274-649] ![]()

This work is a translation and compilation of famous French cooking books, and is thought to be the first example of a compilation and translation of Escoffier.

French-Japanese exchanges in cuisine

Japan also had influence on the traditions of gastronomy. The first Japanese food to arrive in France was soy sauce. It was during the mid-18th century, Kyushu soy sauce was brought to the court of Louis XV (1710-1774) via the Netherlands, and was used dress salad, and quickly spread to courts throughout Europe. There are episodes that nearly 130 years later, when SAIONJI Kimmochi (1849-1940) studied abroad in France, Japanese study abroad students went to a variety of different grocery stores in France in search of and finally succeeding in finding soy sauce (SAIONJI Kimmochi Toan Zuihitsu (lit. The Toan Essays) [97-99] ![]() ).

).

It has already been explained that, although rare, some cooks had already travelled to France during the Meiji and Taisho Eras. However, the period during which Japanese travelled to France to study cooking in the greatest numbers would have been from the 1960's onward. It was during this time that the new trend in French cooking, nouvelle cuisine, was advocated by food critics Henri Gault (1929-2000) and Christian Millau (1928- ), spurring a revolution in the French cuisine world. The traditional strong flavored and heavy food was disavowed, and a move was made towards healthier cuisine which used more refined presentations and took full advantage of the ingredients. Paul Bocuse (1926- ) was known as the "emperor of French cuisine" and was representative of this trend, and in 1972 he travelled to Japan at the invitation of cooking expert TSUJI Shizuo (1933-1993) and held courses for Japanese cooks. All of the major cooks within Japan gathered to participate in these courses. Meanwhile, Bocuse also visited Japanese-style restaurants, including Kiccho, under the guidance of TSUJI, and was fascinated by the presentations and ingredients of the Kaiseki (simple dishes matching the spirit of tea ceremony) he was served. This and the actions of Japanese cooks who travelled to France served as the beginnings of the development of a transition to Japanese-style food in French cuisine.

In 2013, Washoku, traditional dietary cultures of the Japanese, notably for the celebration of New Year, was registered as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage (Gastronomic meals of the French were registered in 2010). There were also number of other happenings related to food too numerous to list, including the publication of a Japanese version of the Michelin Guide. In this manner, the rich food cultures of both Japan and France developed in close relation to each other.