- Kaleidoscope of Books

- Japanese Go—a board game of white and black stones

- Chapter 1: Go in Literary Works: From Ancient to Middle Ages

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Go in Literary Works: From Ancient to Middle Ages

- Chapter 2: The System of Go

- Chapter 3: Learning Go

- Conclusion/References

- Japanese

Chapter 1: Go in Literary Works: From Ancient to Middle Ages

Go is said to have been introduced to Japan from China. There are various theories about its introduction, but Go has appeared in many literary works since ancient times.

In the first chapter, we will focus on documents about Go and Go masters from ancient times to the Middle Ages.

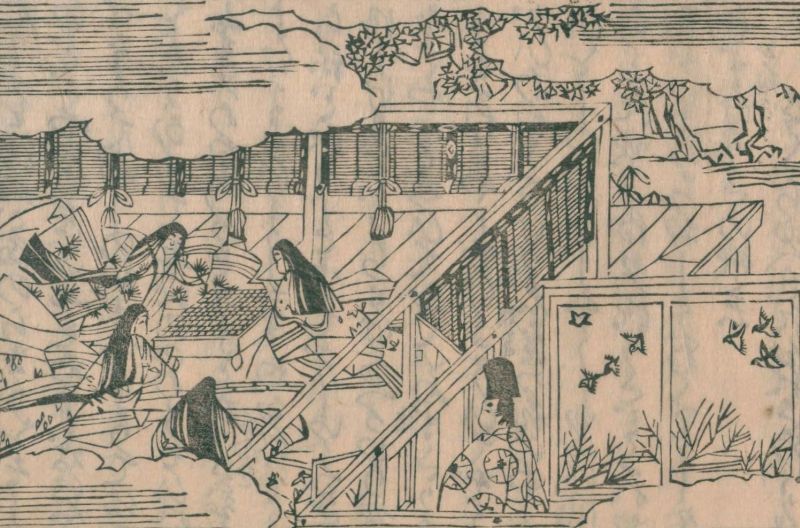

A sketch of the Emperor and Chunagon (vice-councilor of the state) MINAMOTO no Kaoru (中納言源薫) playing Go, from Genji Monogatari Emaki

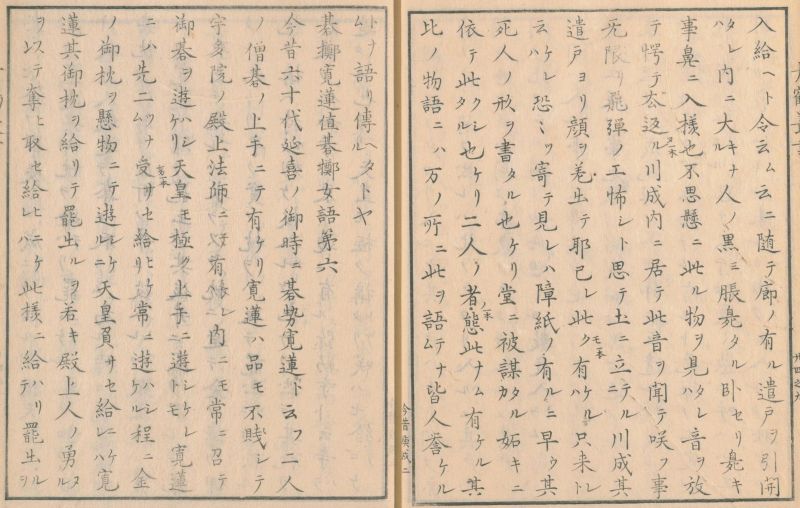

Gosei Kanren

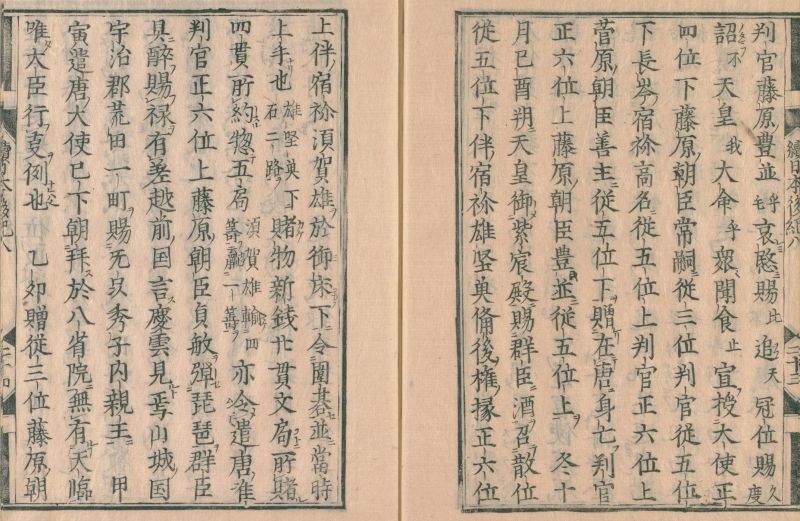

The first appearance in literature of the monk Kanren (寛蓮, 874-?), who was called Gosei (碁聖; lit. Sage of Go), is said to be Seikyuki (『西宮記』) [8 (Special11, banquet, game of Go)] [わ-14] written by MINAMOTO no Takaakira (源高明, 914-982) and dated September 24, 904.

Emperor Daigo (醍醐天皇) invited Kanren and Ushoben Kiyotsura (右少弁清貫) and had them play Go. According to this article, Kanren won the match and was given four rolls of “Kara-aya (唐綾, twill fabric imported from China).” In addition, he was paid a salary for the game.

This article only describes that a feast was held at the Shishinden (紫宸殿, the hall for state ceremonies) in the Imperial Palace and a game of Go was played there. What kind of person was Kanren?

The oldest work in which Kanren is called Gosei is Genji Monogatari (『源氏物語』, The Tale of Genji) [WA7-279], which has a passage saying “there was a time when he was taking on airs like the gentleman they called Gosei” (“Tenarai (手習, Writing Practice)”). It might simply mean a high priest who is a master of Go, but commentaries on The Tale of Genji, including the oldest one, Genji Shaku (『源氏釈』) [KG58-G40], say it refers to Kanren.

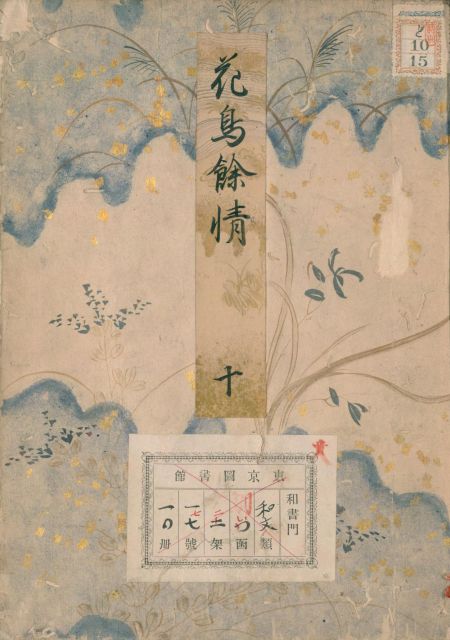

1) Kacho Yosei (『花鳥余情』), written by ICHIJO Kaneyoshi (一条兼良) [と-15]

Kacho Yosei was written by Ichijo Kaneyoshi (一条兼良, 1402-1481) and is a commentary on Genji Monogatari. It is a revised version of the commentary Kakaisho (『河海抄』) written around 1362. Unlike earlier commentaries, the content did not focus on historical research, but instead on understanding the text.

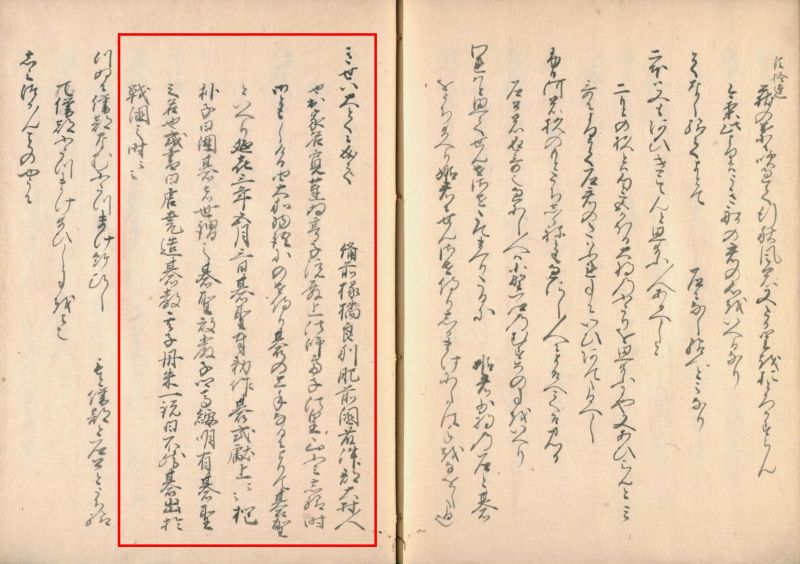

The document describes the part with the Gosei as follows.

Bizen no Jo (備前の掾, Secretary of Bizen Province), TACHIBANA Yoshitoshi (橘良利), was from Omura, Fujitsu-gun, Hizen Province (肥前国, what is now Saga Prefecture). His name as a priest was Kanren and he was a palace priest of Teiji-no-In (亭子院, the Imperial Palace after Emperor Uda’s resignation). According to Yamato Monogatari (『大和物語』), he accompanied Cloistered Emperor Teiji (Cloistered Emperor Uda) walking in the mountains. He was called Gosei because he was a master of Go. On May 3, 913, he made Goshiki (『碁式』, The theory book of Go) by order of the emperor and presented it to the emperor.

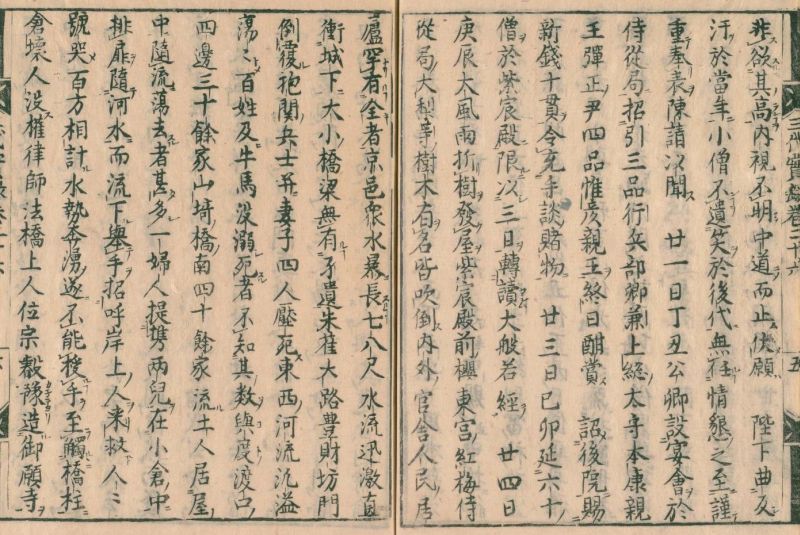

Kanren's anecdote as Gosei was told in Konjaku Monogatari Shu (『今昔物語集』, Tales of Times Now Past) (Tankaku Sosho (『丹鶴叢書』) [117-2]). There are two anecdotes in the passage titled “The Go master Kanren and the story of meeting the Go master woman.” The first one is the story of Emperor Daigo (885-930) and Kanren betting on the “Golden Pillow.” Kanren won the game and founded Miroku-ji Temple (弥勒寺), using the Golden Pillow as capital. The second one is a strange story of Kanren playing against a woman. The following is that story.

One day, while Kanren was on his way from the Imperial Palace to Ninna-ji Temple (仁和寺), which was also the palace of Retired Emperor Uda, he was stopped by a girl and asked to play a match of Go at a certain residence. He played the match, however, as it went on, the stones of Kanren became almost annihilated. Kanren run back to Ninna-ji Temple. The retired emperor heard what happened to Kanren, and felt suspicious. So he sent an envoy to the residence the next day. In the residence, there was only an elderly nun. As for the woman who had been there the night before, the envoy could only discover that she had come for katatagae (方違, old practice of reaching a destination by taking a different direction than going directly from one’s house, by putting up somewhere the night before) as part of tsuchiimi (土忌, in Onmyodo, the action of avoiding construction that violates the earth, such as building, in a certain place or direction). When the retired emperor heard about it, he thought it was strange, and he suspected that Kanren must have had a match with a monster.

This story may have been influenced by an episode about a master of Go named Wang Jixin (王積薪) in a collection of odd stories from the Tang Dynasty in China called Shuiki (『集異記』) [1-2224]. At an old woman's house in the mountains, where Jixin stayed for the night, he heard the landlady and her mother-in-law playing Go orally in the dark. The next day, after receiving a lesson from the woman, he left the house, but when he tried to go back to it, he found it had disappeared. The name of Wang Jixin can be found in the poetry of SUGAWARA no Michizane (菅原道真, 845-903), who was a contemporary with Kanren, and it seems that Wang Jixin was already known in Japan at that time. It suggests that the anecdote of Konjaku Monogatari Shu was inspired by the anecdote of Wang Jixin.

Women and Go

In the previous section, we introduced the word Gosei in The Tale of Genji. There are many descriptions about Go in literary works created by women in this period. In The Tale of Genji, Go appears in chapters other than “Tenarai (手習, Writing Practice).” In the chapter “Utsusemi (空蝉, The Cicada Shell),” there is a scene where two women, Utsusemi (空蝉) and Nokiba no Ogi (軒端荻, Utsusemi’s daughter-in-law), are playing a game of Go. In this story, there were casual exchanges between the two including Go terms. This suggests that Murasaki Shikibu (紫式部, the author) had a background in Go, and that the readers of the story naturally understood these exchanges. Also, in the chapter “Takekawa (竹河, Bamboo River)”, there is a scene where the daughters of Tamakazura play Go for the cherry blossoms in the garden and, in the chapter “Yadorigi” (“宿木, The Mistletoe”), there is a scene where the Emperor plays against Chunagon Minamoto no Kaoru(中納言源薫).

This is an ukiyo-e woodblock print depicting a scene in The Tale of Genji in which two women play Go together. This is a type of picture called a mitate-e (見立絵), which represents well-known classical subjects in a contemporary style.

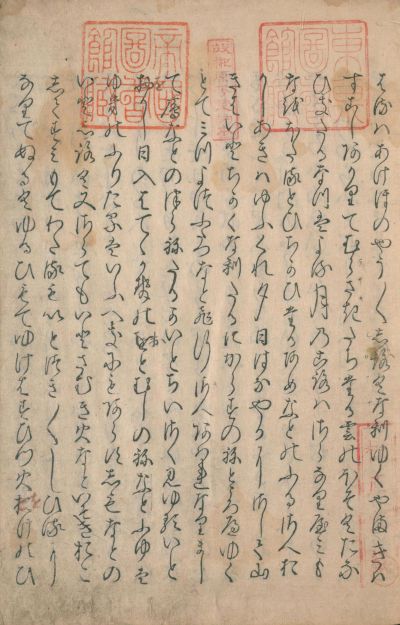

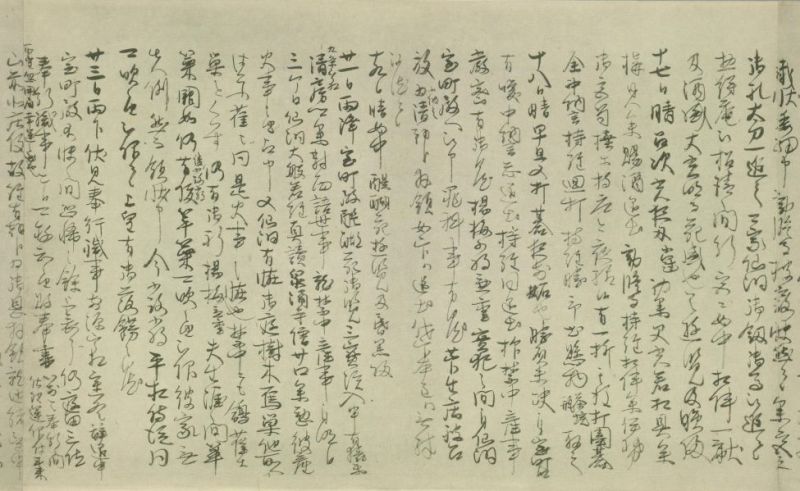

2) The Pillow Book (『枕草子』), written by Sei Shonagon (清少納言) during the Kan’ei era [WA7-141]

The Pillow Book, written by Sei Shonagon (966?-1025?) is one of the two most outstanding literary works of the Heian period, along with The Tale of Genji. Let's take a look at the scene of Go there.

In the section of “Elegantly intriguing things (心にくきもの),” it says that the sound of Go stones dropping into the box is fascinating and elegant.

The most interesting point about this book is how the author feels when playing Go. The following passage from “People who look pleased with themselves (したり顔なるもの)” is one such scene.

“While an opponent sticks to placing stones badly on some area with greedy attempts, I feel so happy to be able to take much more area of a different part of the board, feel much more proud than just a win, and laugh so loudly with pride.” Sei Shonagon writes frankly about how she feels playing Go.

On the other hand, there is a different passage about her failure. “I tried to place a stone and took my opponent's area with my face delighted. However, I failed and the opponent's stone was alive. I felt as if my stone was dead and taken away.” From these descriptions of both sides, you can imagine clearly how the author played the game.

Let me give you one more example, which is not of an actual match, but in which Go terms are the key. It is a description of some exchanges between the author and FUJIWARA no Takanobu (藤原斉信) and MINAMOTO no Nobukata (源宣方). They use Go terms such as “being into the final stones” and “breaking up the board” as metaphors for relationships between men and women, such as lovers who had become “already intimate” and “very close.” It suggests that, the same as The Tale of Genji, rules and words related to Go were shared among aristocrats in those days.

Go and bets

In ancient times, there are many records of people betting money and goods on Go matches. For example, the following is a record of a game of Go held in front of Emperor Ninmyo (仁明天皇, 810-850) in October 839.

The emperor came to Shishinden and gave sake to his retainers. The emperor invited TOMO no Sukune Okatsuo (伴宿祢雄堅魚) and TOMO no Sukune Sukao (伴宿祢湏賀雄) to play a Go match. Both of them were masters of Go of that time. The stakes were 20 kan (an old unit of currency) of new money (they bet four kan per game and played 5 games in total). (Sukao’s record was 1 win and 4 loses)

In this way, money was bet on each game.

There is also a record in Nihon Sandai Jitsuroku (『日本三代実録』, Veritable Records of Three Reigns of Japan) [839-4] that money was bet on a game of Go. According to a description dated August 21, 874, it is stated that “The court noble invited the imperial prince to the Goin Palace (the Retired Emperor's Palace), gave 10 kan of new money, and had him allocate it for Shudan gambling.” Shudan (手談) is an elegant name for Go, and this description is said to be the first appearance of the word Shudan in Japanese literature.

After that, the money people bet on Go was called Gotesen (碁手銭) or Gote (碁手) in Japan. It gradually took on the meaning of a congratulatory gift on auspicious occasions. For example, in The Tale of Genji (“Yadorigi” (“宿木, The Mistleote”)), there is a description that “As is the custom, the celebration on the third night was private. On the fifth night, Kaoru sent fifty servings of ceremonial rice, prizes for the Go matches, and other stores of food, as custom demanded.” This example suggests that it was a custom at that time to send prizes for Go matches as a gift.

Furthermore, looking at the diaries of court nobles in the Muromachi period (1336-1467) and the Sengoku period (1467-1590), there are many descriptions that money and goods were bet on games of Go. As an example, in an article from Kanmon Nikki (『看聞日記』 [貴箱-14]) dated February 17, 1431, written by Imperial Prince Fushimi no Miya Sadafusa (伏見宮貞成親王, 1372-1456), it is stated that “After that, we played Go. I played Go with Chunagon (vice-councilor of the state) Mochitsune. Mochitsune won the game. I took out a prize (tea bottle), and he received it.” Indeed, seeing records from the medieval period, we can see that gambling often appears in scenes where court nobles and samurai gather together to compete for superiority. It can be said that betting on games of Go was one of them.

The game of Go in waka, classic Japanese short poems

Go has appeared in prose and poetry since ancient times. Among these appearances, there are examples of words derived from Go being used differently from their original meaning.

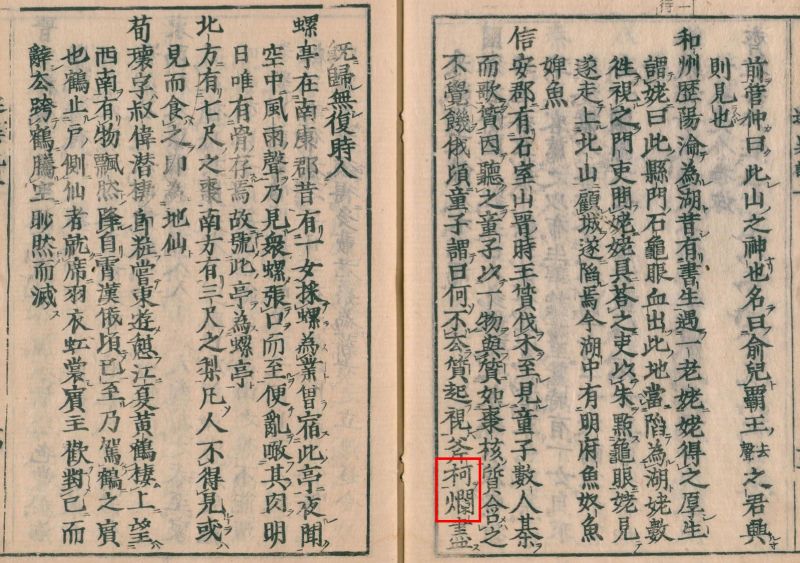

One of them is the word “ranka (爛柯),” which is the title of the book we will cover in Chapter 2. The word originated in ancient China and can be found in a document called Jutsuiki (述異記, Tales of strange matters) [853-223]. During the Jin Dynasty, a man named Wang Zhi went to Mt. Shishi in Xing'an County (present-day Quzhou City, Zhejiang Province) to cut wood. When Wang Zhi saw several youths playing Go and singing, he stopped to listen. A moment later, a child said, “Why don't you go home?” When he looked at his ax handle (柯, ka), it had rotted away (爛, ran). When he returned home, he saw no one from his own time.

The word “ranka” as a metaphor for losing track of time in the game of Go first appears in Japanese poetry in the imperial collection of Chinese poetry, Keikokushu, established in 827 (『経国集』, Chinese style poem collection for managing the country, edited by SHIGENO no Sadanushi. [寄別15-5] ).

After that, the following waka was included with kotobagaki (the headnote of a short Japanese poem) in Kokinshu (『古今集』) (Volume 18, Zoka (Miscellaneous poems) 2nd) [き-15], which is the first imperial anthology of Japanese poetry.

When he was in Tsukushi, Tomonori sent this poem to the home of a friend where he had often gone to play Go, telling him that he would be returning to the capital.

Home at last and yet

it is not what it once was

to me now that I

long for that place of exile

where the ax handle crumbled

KI no Tomonori (紀友則)

Also, the following waka were selected for Gosen Wakashu (『後撰和歌集』, Later Collection of Japanese Poems) (Volume 20 Felicitations) [837-2], which is the second imperial waka anthology.

In the Imperial Palace, Kiyoko was offered a Go board by Miya no Onkata. Looking at the lid of the Go box, she made a waka poem.

Even if your ax handle

completely rotted away,

until your life

comes to the very end,

let’s enjoy the game of Go

Myobu no Kiyoko (命婦清子)

Other waka poems with “the ax handle” are included in Gosen Wakashu, but its usage shifted away from Go and came to be used as an expression for “a long time having passed.”

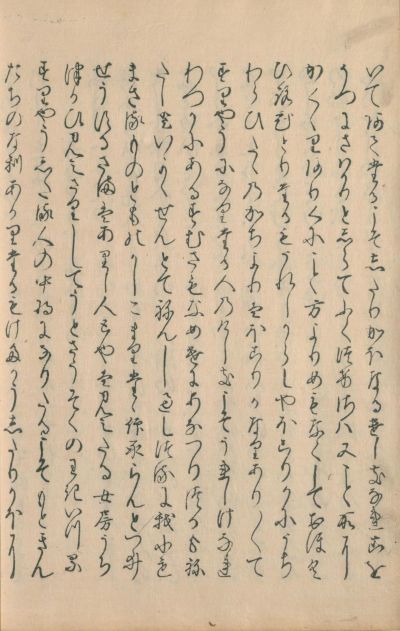

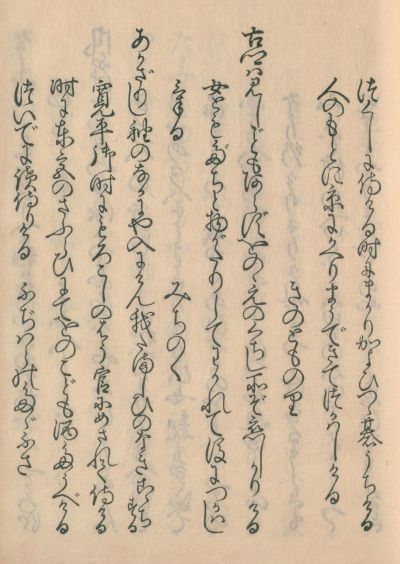

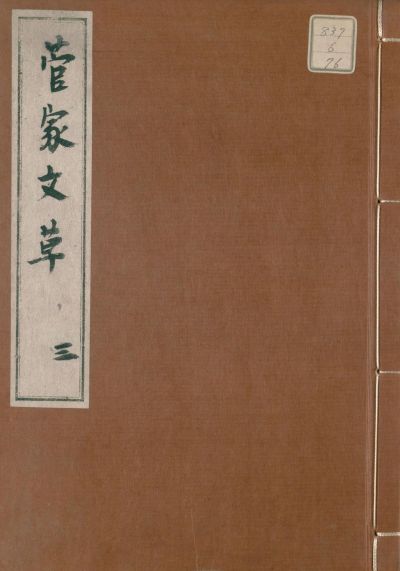

3) Kanke Bunso(『菅家文草』), written by SUGAWARA no Michizane, published by NODA Tohachi in 1700 [837-76]

Kanke Bunso is a collection of SUGAWARA no Michizane's Chinese poems that were presented to Emperor Daigo in 900. It consists of 12 volumes, including poetry in the first six volumes and prose in the second six volumes. Five poems related to Go are included in this collection.

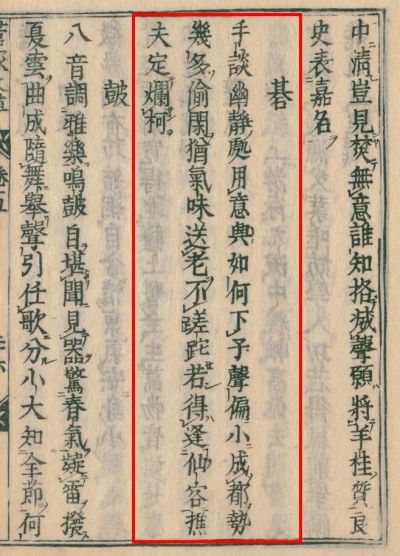

Here are some of the poems from Volume 5. The materials in the National Diet Library are printed books, so the title is “Go (碁)”, but in old manuscripts in the Sonkeikaku Bunko (尊経閣文庫) and other collections, the title is "Igo (囲碁)”.

“Go”

手談幽静處 (The two hands talk in a quiet place.)

用意興如何 (What fun it is to think about what to do.)

下子聲偏小 (The sound of placing Go stones on the board is very small.)

成都勢幾多 (The momentum to form territory like a city with stones is magnificent.)

偸閑猶気味 (Playing Go in one’s spare moments when you are busy is also interesting.)

送老不蹉跎 (Even if you get old, you would not be senile by playing Go.)

若得逢仙客 (If I could see hermits playing Go)

樵夫定爛柯 (I am sure I would rot away my ax handle like the woodcutter did.)

In the beginning, the scene of a quiet match is presented. In contrast, as the stones are placed, a large territory is built on the board. He preaches about the “utility” of Go, saying that it is tasteful to play Go in one’s spare time, and that you would not become senile if you play Go when you get old. He concluded his poem with an anecdote about ranka.

Next Chapter 2:

The System of Go