- Kaleidoscope of Books

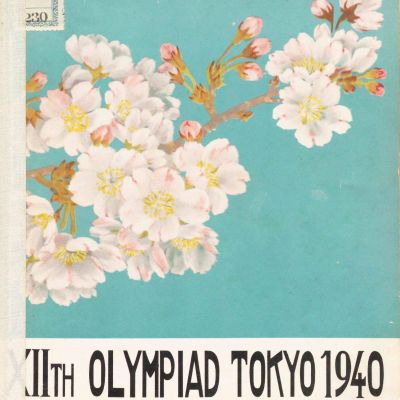

- The Lost Tokyo Olympics of 1940

- Chapter 2: Tokyo’s bid to host the Olympics

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Japan’s participation in the Olympic Games

- Chapter 2: Tokyo’s bid to host the Olympics

- Chapter 3: The outbreak of war and cancellation of the Olympics

- Chronology

- Conclusion/References

- Japanese

Chapter 2: Tokyo’s bid to host the Olympics

Japan’s Olympic team had grown in size and continued to capture more and more medals at each successive Olympics, while overcoming not just a lack of experience at international competition but also funding problems. And with this increasing success, the interest of the Japanese public in the Olympics was growing.

Japan reached a new milestone when Tokyo sought to become the first Asian city to host the Olympics with its bid to host the 12th Olympic Games in 1940.

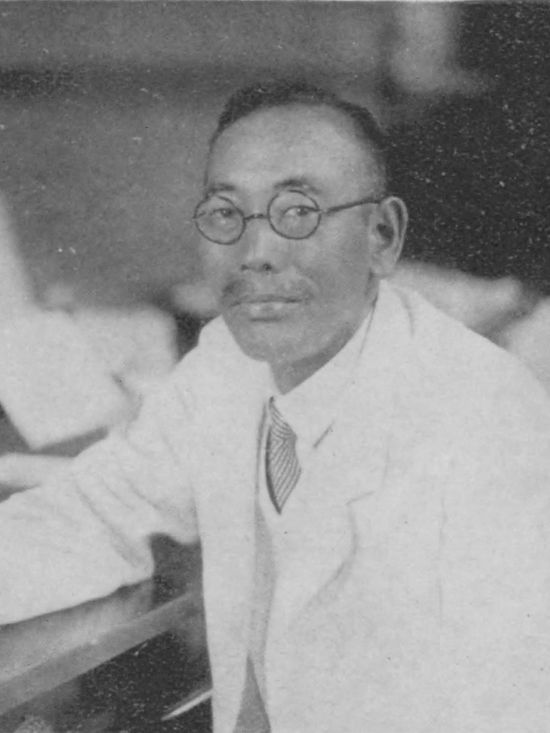

The ambitions of Nagata Hidejiro

In 1929, Sigfrid Edström, who as chairperson of the International Association of Athletics Federations, came to Japan to talk with YAMAMOTO Tadaoki, chairperson of the Inter-University Athletics Union of Japan, and one of the topics they discussed was the possibility of Tokyo hosting the 12th Olympic Games in 1940.

NAGATA Hidejiro, who became Mayor of Tokyo City in 1930, was also present at these discussions and became the first to promote Tokyo as a venue for the Olympics. Learning that Yamamoto was scheduled to leave for Germany at the head of Japan’s delegation to the International Student Athletic Championships, Nagata asked Yamamoto to look into what the European sporting world’s response to a bid from Tokyo for the 12th Olympics might be.

What was behind Nagata’s idea to host an Olympic Games in Tokyo? He had heard Edström and Yamamoto agree that Tokyo did have a chance of hosting the games should it make a serious bid. Moreover, the year 1940 coincided with the 2600th anniversary of the ascension of Emperor Jimmu, an occasion for which a variety of commemorative events were certain to be organized. Nagata felt that the Olympic Games was perfect for just such an event.

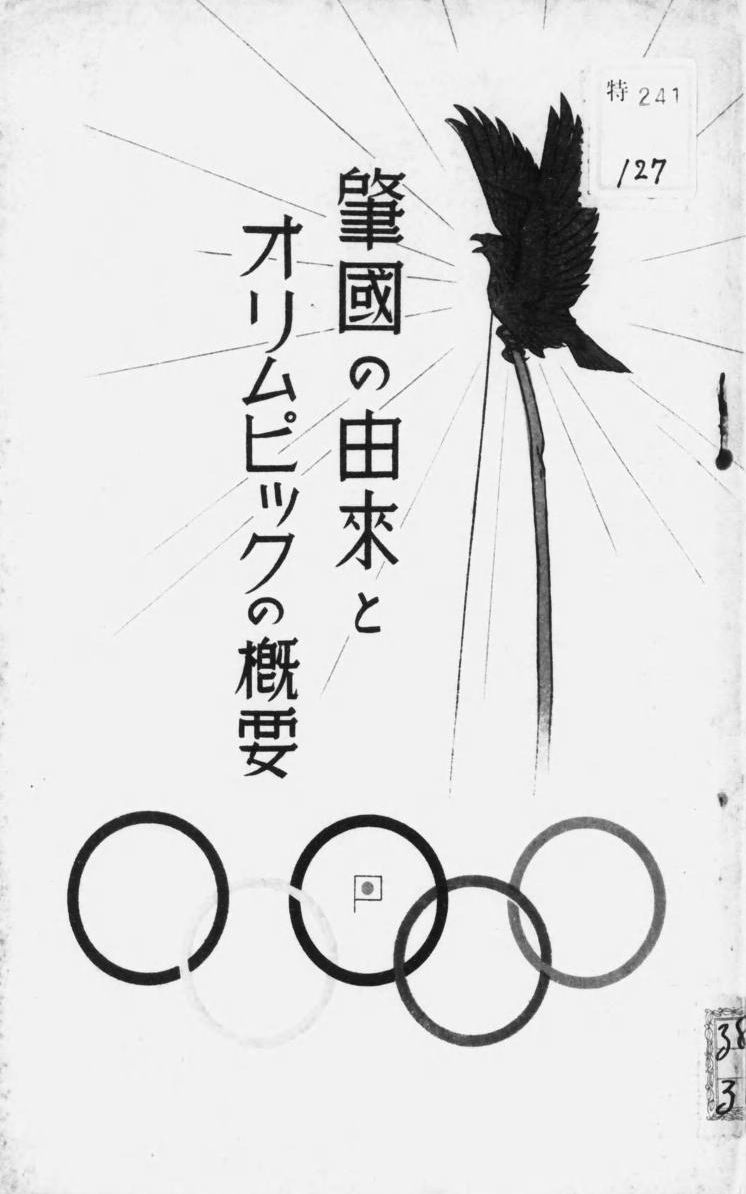

4) Chokoku no yurai to Olympic no gaiyo (the founding of Japan and a general outline of the Olympics), Kigen 2,600 nen Teito Kankokai, 1937. [特241-127]

The word chokoku refers to the founding of a nation. Chokoku no yurai to Olympic no gaiyo was written to promote events planned to celebrate the 2600th anniversary of the imperial era, in which context it also touches on the significance of holding the Olympic Games in Tokyo.

For example, the book states that the five interlocking rings comprising the Olympic logo represent the five continents of the Earth—Europe, Africa, Asia, Australia, and the Americas. And it goes on to explain that “until now, the Olympics have been held only at either end of the five rings: Europe and America. Therefore, the Olympics should now be held in the center ring, which is Asia, for it is the utmost duty of the Japanese people to bring the Olympic flame, which embodies love for all humankind, to Tokyo and to host the Olympic Games in a manner that reflects our unique ethnic identity.”

Thus, in July 1932, the two IOC members from Japan—Kano Jigoro and KISHI Seiichi—submitted to the 30th IOC session in Los Angeles an official proposal from Tokyo to host the 12th Olympic Games.

At the time, nine other cities in Europe and America were competing with Tokyo to host the Olympics. Faced with stiff competition, Kano and Kishi sprang into action.

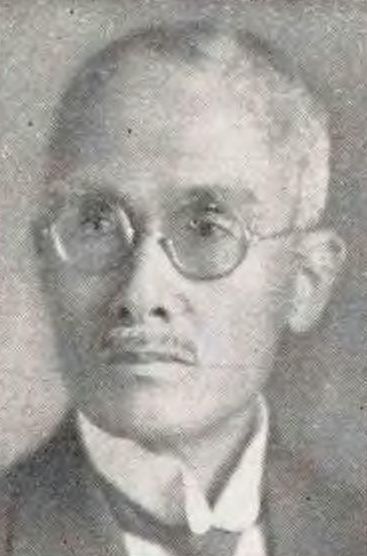

Kishi Seiichi’s vision

Kishi Seiichi served on the IOC from 1924 until his death in 1933, during which time he worked tirelessly to promote sports in Japan. Although a lawyer by profession, he had been an avid rower since his days as a student at the Imperial University. He was not only the first chairperson of the Japan Rowboat Association but also the second chairperson of Japanese Sport Association established by Kano Jigoro and worked to get the Japanese Soccer Association enrolled in FIFA. His efforts contributed greatly to the promotion of competitive sports in Japan.

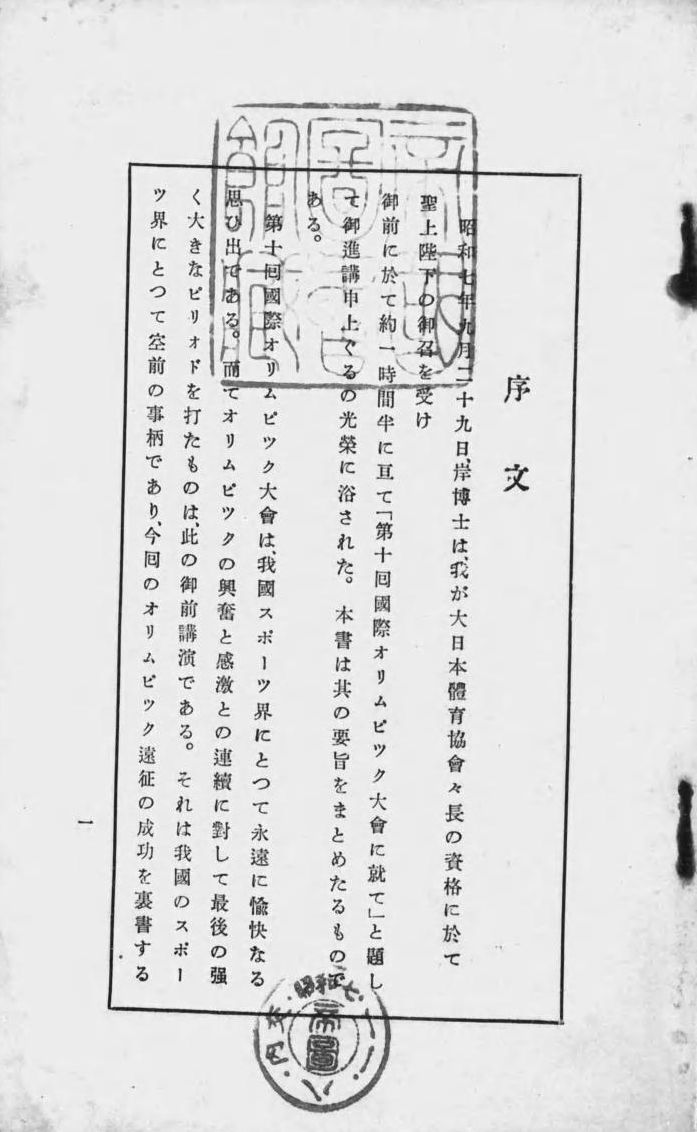

5) Kishi Seiichi, Dai 10 kai kokusai Olympic Taikai ni tsuite (the 10th international Olympics), Japan Sports Association, 1932. [特234-682]

In addition to being a member of the IOC, Kishi held a number of other important posts, as well. The Emperor requested that he serve as chairperson of the Japan Sports Association. Dai 10 kai kokusai Olympic Taikai ni tsuite contains a summary of a lecture that Kishi gave on September 29, 1932, about the Games of the X Olympiad, which were held Los Angeles.

Kishi recognized that it would be difficult to win the bid to host the 12th Olympics, and pointed to an enthusiastic bid by the city of Rome, which had nearly finished constructing the planned facilities.

Japan was also at a disadvantage in terms of both geography and climate. Thus, Kishi and Kano scrambled to rationalize Tokyo’s bid by emphasizing that “Olympics should be held in Asia as well as in Europe and America.” Although a number of key personalities came out in support of Tokyo’s bid, the Japanese were not optimistic.

For example, although the 11th Olympic Games had been awarded to Berlin in 1931, the Nazi party was apparently not interested in hosting the Olympics, and a tacit agreement was in place that, should the Nazis come to power in Germany, the games would be held in Rome instead of Berlin.

Kishi’s view of the situation was that “Tokyo might get the 12th Olympics as long as we maintain our momentum with continued effort. Given the agreement that is in place, however, it could be difficult to defeat Roma and bring the 12th Olympics to Tokyo unless the political situation in Germany changes.”

The situation did, in fact, change when the Nazis came into power in 1933, and Hitler decided to use the Olympics as a showcase for Aryan superiority. Consequently, the 11th Olympic Games were held as scheduled in Berlin, so Rome did not withdraw its bid to host the 12th Olympics.

Kano Jigoro and the Olympic campaign

Kano Jigoro also contributed to the campaign to host the Olympics, not just at official events in his capacity as a member of the IOC but also informally lobbying IOC members. He argued strongly at every opportunity to emphasize the significance of hosting the Olympics in Tokyo, saying “the modern Olympics are not limited just to Greek athletes but include athletes from all over the world. So too should the hosting of the Olympics not be limited to Europe or America, and Japan is as passionately involved as Europe and America.”

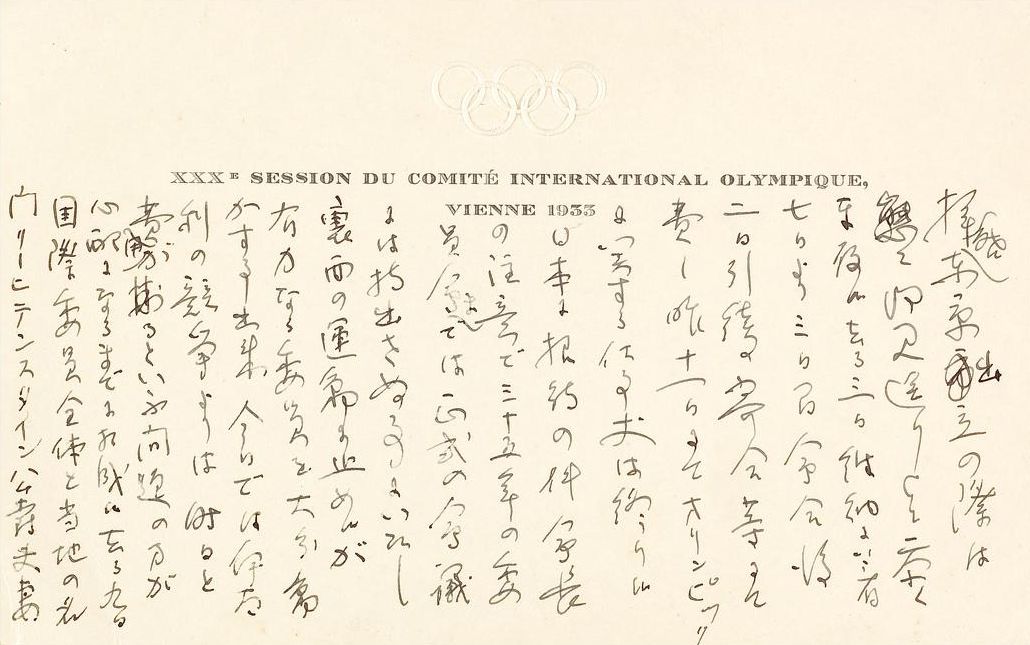

6) Showa 8 nen 6 gatsu 12 nichi zuke Nagata Hidejiro ate Kano Jigoro Shokan (letter from Kano Jigoro to NAGATA Hidejiro, dated June 12, 1933). [Nagata Hidejiro and Ryoichi Related Document 201-2]

This letter was sent from Kano to Tokyo Mayor Nagata in June 1933, while Kano was attending an IOC general assembly in Vienna.

In the letter, he describes inviting everyone from the IOC as well as prominent members of the Viennese aristocracy to a banquet, during which he was able to increase support for Tokyo’s bid. He came away from this event feeling confident that “we need to worry more about the timing and the cost of the games than about competing with Italy.”

He also wrote that, although the chairperson of the IOC was reluctant to increase the number of IOC members from Japan, a former ambassador of Turkey as well as Chairperson Sigfrid Edström of the International Association of Athletics Federations was supportive, and Japanese diplomat Sugimura Yotaro was able to join the IOC. Anecdotes such as this one indicate Kano’s strong connections with people who were in a position to support Tokyo’s bid.

<Translation>

Dear Sir,

Thank you for seeing me off when I left Tokyo.

I arrived at Vienna on the 3rd, spent the 7th, 8th, and 9th attending an IOC session, and another two days after that at other gatherings, finishing my work for the Olympics yesterday on the 11th.

The chairperson has warned us not to raise the subject of Japan’s bid at a formal session until the 1935 session. But we have informally met with many influential people, and right now I think we need to worry more about the timing and the cost of the games than about competing with Italy.

On the 9th, we invited probably 70 influential people, everyone from the IOC as well as prominent members of the Viennese aristocracy, including the Duke and Duchess of Liechtenstein as well as and Duke and Duchess of Kinsky, for a banquet. It was one of the most successful parties in years and the number of people who feel sympathetic to Japan has increased.

We raised the issue of increasing the number of IOC members from Japan to three. And while the chairperson was not sure, former Turkish ambassador General Celil and Chairperson Edström from Sweden took our side. Our recommendation of Sugimura Yotaro as a third member was passed unanimously. I think it will be an advantage for us at the session in 1935.

That’s all.

Sincerely yours,

June 12, Kano Jigoro

A secret agreement between Soejima Michimasa and Mussolini

Although support for Japan had increased, the Roman bid was still a concern.

Count Soejima Michimasa, who was both an entrepreneur and a former member of the House of Peers, was asked to tackle the difficult problem of requesting that Rome withdraw its bid. Having replaced Kishi on the IOC, he went to Rome to negotiate in 1934, but came down with a serious illness just before he was scheduled to meet with Italian Prime Minister Mussolini. Meeting with Mussolini despite his illness, he explained Tokyo’s bid in the context of Japan’s planned celebration of the 2600th anniversary of the founding of the Imperial House and requested that Rome give way to Japan. Sympathetic to the celebration of an imperial dynasty, Mussolini agreed to have Rome withdraw its bid. No sooner had he done so, however, than the Italian Sports Association took the opposite stance and insisted the Roman bid stand.

Soejima once again appealed to Mussolini, who ordered the Italian members of the IOC in Oslo to withdraw the bid unconditionally.

Although Italy made a statement at the IOC session announcing that Rome would withdraw its bid in consideration of Japan’s ambitions to hold the 1940 Olympics in Tokyo, this abrupt cancellation threw the general session in Oslo into confusion.

There were some who continued to support Rome’s bid even though it had been withdrawn. Not wanting to create more controversy by deciding on a host city right away, the vote was postponed until the scheduled session in Berlin in 1936.

Inspection of Japan by the IOC chairperson

One reason that the vote to decide on a host city was suspended was because IOC Chairperson Baillet-Latour was opposed to holding the Olympics in Tokyo. He was displeased that Japan had not correlated with the IOC in negotiating directly with the Italians.

On April, 1935, two months after the Oslo session, Soejima received a letter from Latour. According to a Report on the 12th Olympic Games Tokyo Organizing Committee [779-51], Soejima recalled that the letter bemoaned “poor sportsmanship on the part of Japan, which negotiated directly with Rome without correlating their actions with the executive members of the IOC.” But went to say that “if Japan respects the spirit of the Olympic Charter from now on, I will make an effort on behalf of Soejima.”

Given that the vote had been postponed, the prevailing sentiment in Tokyo was that it would be prudent to increase support for Tokyo’s bid. Wanting to meet with executive members of the IOC, they invited Latour to visit come Tokyo, and he arrived in March 1936.

A welcoming committee was set up, and when Latour arrived at Japan, the major of Tokyo as well as numerous people involved in sports were there to greet him. Not only that, but a good number of the general public were there, too, when Latour’s ship came into port. The Report on the 12th Olympic Games Tokyo Organizing Committee [785-25] quotes Latour as saying “When I arrived at Yokohama, elementary school children were there to welcome me with Olympic flags. This shows me the deep understanding that the Japanese people have of the Olympics as well as of sports in general, and I am very satisfied.”

After spending a busy two weeks in Japan, touring a variety of facilities and attending banquets, Latour headed for home in fine spirits.

As he departs, Latour shakes hands with Tokyo Mayor USHIZUKA Torataro

(To the right of Ushizuka is Kano.)

The selection of the host city

Thanks to the efforts of IOC members such as Kano and Soejima as well as the activities of the Tokyo municipal and the Japanese national governments, Tokyo’s chances of being selected as host city were higher than ever.

On July 31, 1936, an IOC session was held in Berlin to decide between Tokyo and Helsinki, which were the only two candidates remaining. At 3:00 p.m. local time the IOC met behind closed in the Hall of Mirrors at the Hotel Adlon, one of Berlin’s most exclusive hotels.

At 18:45 the IOC opened the door and came out, announcing “Tokyo!” as he descended the stairway. Needless to say, the Japanese delegation was ecstatic.

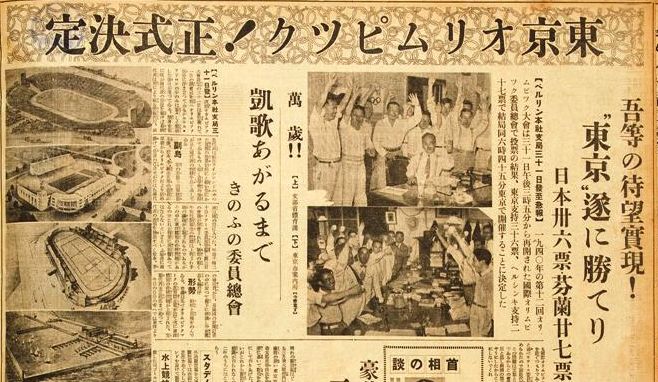

7) “Tokyo Olympic! Seishiki Kettei (It’s official! The Tokyo Olympics!),” Asahi Shimbun, Tokyo, August 1, 1936, morning edition, p. 2. [Z81-1]

This article appeared in the morning edition of the Asahi Shimbun for August 1, 1936, the day after the host city was decided. It reported that Tokyo was chosen over Helsinki by a vote of 36–27 and described the atmosphere of the IOC session as well as the demeanor of Kano, Soejima, and other members of the Tokyo Organizing Committee.

We can discern the different personalities from descriptions such as “Kano is as optimistic as always, while Soejima is worried about the impact of yesterday’s publications by Finland.”

The article also devotes a large space to describing the reactions of many Japanese: workers from the Tokyo city hall are excited as they toast the Olympics with beer, Tokyo Mayor Ushizuka expresses his approval, and Japanese Prime Minister HIROTA Kouki feels that Japan has rightly gained the world’s understanding. It also includes a message from former mayor of Tokyo Nagata, who initiated Tokyo’s bid, and a picture of him wearing a big smile.

Next

Chapter 3: The outbreak of war and

cancellation of the Olympics