- Kaleidoscope of Books

- The Lost Tokyo Olympics of 1940

- Chapter 1: Japan’s participation in the Olympic Games

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Japan’s participation in the Olympic Games

- Chapter 2: Tokyo’s bid to host the Olympics

- Chapter 3: The outbreak of war and cancellation of the Olympics

- Chronology

- Conclusion/References

- Japanese

Chapter 1: Japan’s participation in the Olympic Games

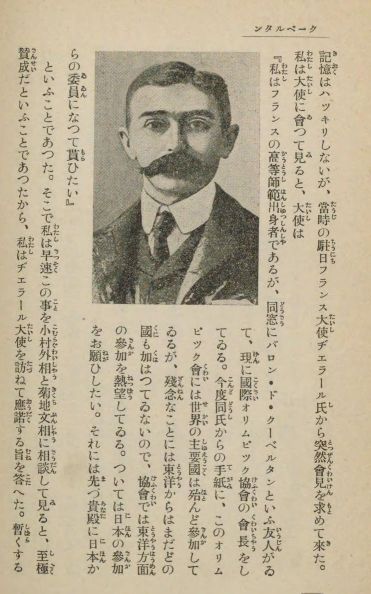

The modern Olympic Games were first proposed in 1892 during a lecture at the University of Paris 1 Pantheon-Sorbonne by the French educator Baron Pierre de Coubertin, based on his idea to revive the games that had been held every four years at Olympia in ancient Greece. To further this idea, he described the Olympic Games as a means to promote world peace though athletic competition, and gradually won support from a number of influential figures. In June 1894, during an international conference to advance the development of sports that was held at the University of Paris, an International Olympic Committee (IOC) was formed to revive the Olympic Games.

A mere two years later, in 1896, the first modern Olympic Games were held in Athens, starting a tradition that continues to this day despite interruptions due to two world wars.

Japan’s first participation in the Olympic Games

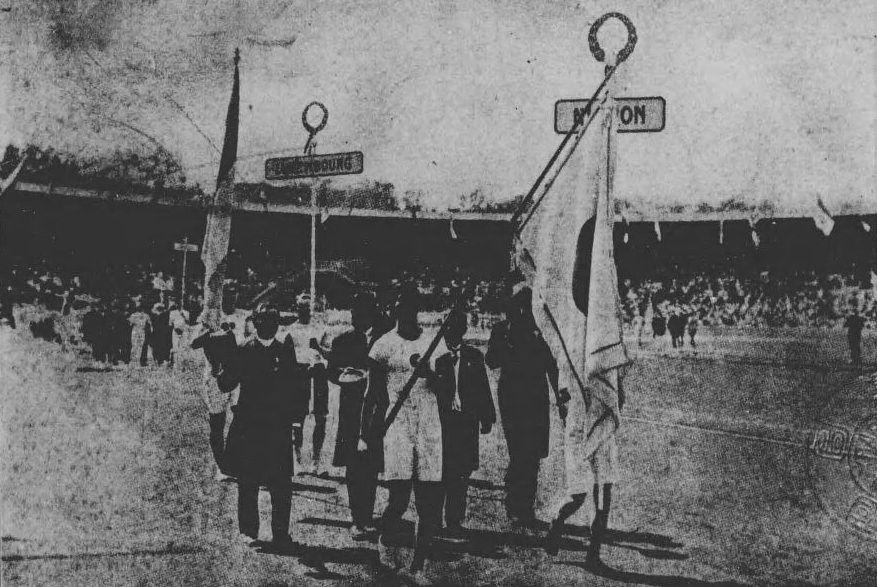

Japan first participated in the Olympic Games during the 5th Stockholm Olympics in May 1912.

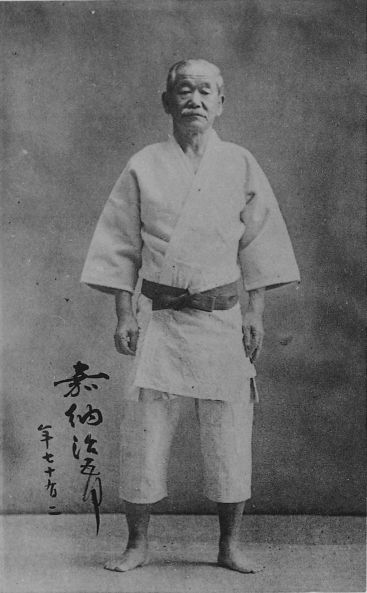

IOC President Coubertin was actively seeking to internationalize the event, because no country from Asia had participated until the 4th London Olympics. In 1908, he requested Auguste Gérard, French Ambassador to Japan, to recommend someone to represent Japan at the IOC. KANO Jigoro, the founder of Kodokan Judo, was recommended, due to his knowledge of sporting events and proficiency at foreign languages. Accordingly, at the IOC general assembly the following year, Kano was named the first Asian member of the IOC.

In 1911, Kano established the Japan Amateur Athletic Association to organize a team of Japanese athletes to participate in the Olympic Games, and qualifying games were held at Haneda in November of the same year. Kano also participated in the Stockholm Olympics as a captain of the Japanese team.

Two players from Japan qualified for the Stockholm Olympics: sprinter MISHIMA Yahiko participated in the 100-, 200-, and 400-meter races, while KANAKURI Shiso took part in the marathon. Mishima failed to qualify for either the 100- or the 200-meter races, and retired due to fatigue during the 400-meter semifinals. Likewise, Kanakuri dropped out of the marathon due to dehydration.

This less than auspicious debut in international sports served to highlight not just the gap between Japanese athletes and their counterparts around the world but the major issue of how to further develop sports in Japan.

1) Sekaijin no Yokogao (profiles of world figures), Asahi Shimbun, Shijo Shobo, 1930. [578-337]

This book contains articles from the Asahi Shimbun about various world figures. It includes an article written by Kano about Coubertin. In the article, Kano repeatedly used the word “kindness” and said that he had a very good impression of Coubertin. He also wrote that “the development of sports in Japan was due to a number of factors, but we should not overlook the fact that Coubertin brought Japan into the Olympics.” Clearly, participation in the Olympic Games had a major impact on Japanese athletics.

This book is very interesting because it contains articles on people such as painter YOKOYAMA Taikan, Italian Prime Minister Benito Mussolini, actor HAYAKAWA Sessyu, auto tycoon Henry Ford, physicist NAGAOKA Hantaro, and UK Prime Minister Arthur Balfour.

Hardships sending athletes

Although we say that “Japan participated in the Olympics,” the reality is that each athlete had to pay the 1,600 yen cost (about 4 million yen in today’s currency) of attending themselves. For this reason, Kanakuri Shiso originally declined to participate. Kano Jigoro was a director of the Tokyo Higher Normal School, where Kanakuri was employed, and was able to form a supporters group to raise the money.

The Japan Amateur Athletic Association (JAAA) set up an organization for promoters and supporters and raised as much money as it could, but could not acquire enough funding to cover costs. Although the 6th Berlin Olympics were called off because of World War Ⅰ, the JAAA struggled again when trying to send athletes to the 7th Antwerp Olympics in 1920.

A request that the Japanese government subsidize these expenses was also refused, because the government did not consider sports to be popular enough to deserve the support of all Japanese people. The JAAA scrambled to raise 20,000 yen and continued efforts to obtain additional funding even after the athletes had departed for the games. Executive board members were able to obtain annuities from both the Mitsui and the Iwasaki zaibatsu, which provided the 30,000 yen needed to cover all expenses. And when the Olympic team stopped in New York and London on their way to Antwerp, director TATSUNO Tamotsu was able to gain additional support from Japanese expatriates. (The History of Japan Amateur Athletic Association, vol. 1, edited and published by the Japan Amateur Athletic Association, 1936–1937 [722-53])

At the games, KUMAGAI Ichiya won a silver medal in the men’s single tennis competition and then teamed up with KASHIO Seiichirou to win a silver medal in men’s doubles. These were the first Olympic medals won by Japanese athletes, which provided an impetus for the Ministry of Education to accept a request for government support of the 5th Far Eastern Championship Games* the following year. Moreover, the Government allocated 60,000 yen (about 70 million in today’s money) in subsidies to send athletes to the 8th Paris Olympics.

*The Far Eastern Championship Games began in 1913 and were held a total of ten times until 1934, with Japan, China, and the Philippines being the main participants.

Interaction with foreign athletes

Competing in the Olympics made it clear that few Japanese athletes were ready to appear on the world stage. As Japanese athletes began to participate in international sporting events, many of the events held in Japan made a point of inviting foreign athletes to participate.

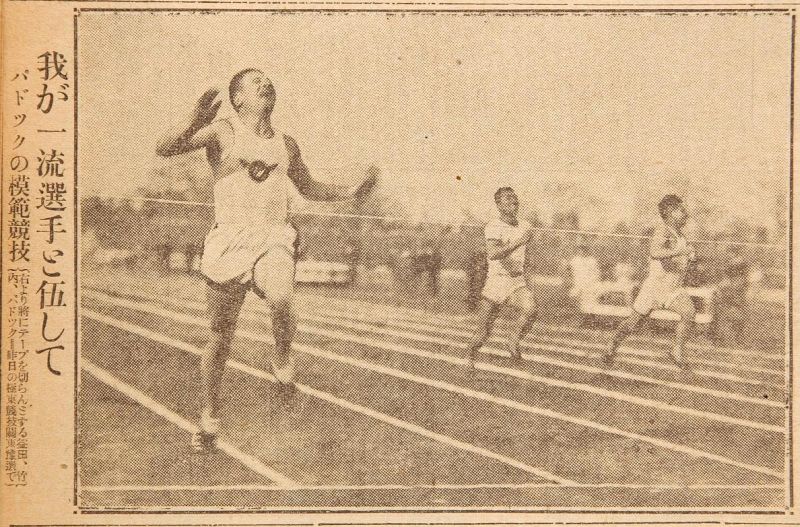

In April 1925, Japan invited two of the world’s best sprinters from the United States, Charles Paddock and Loren Murchison, to give Japan’s slumping sprinters a boost.

Assembling the winners of preliminary rounds at the Far Eastern Championship Games, they coached and competed on a special track at Osaka’s Koshien stadium on April 7 in front of large crowds who sought a glimpse of world-class athletes. They also coached runners in Tokyo before leaving Japan on April 21. Still, many of the Japanese athletes were simply not ready to compete at the world level.

Some international swimming competitions were held, such as the one between Japan and Hawaii in September 1926, and games between Japanese and American athletes were hosted by the Houchi Shimbun in September 1927, both in Tokyo and in Osaka. Five Japanese athletes participated in the US championships in Hawaii that same year, and there were other international sporting events in rugby, basketball, and tennis, too.

Success at the 9th Amsterdam Olympics in 1928

Although Japanese athletes had won two silver medals at the 7th Antwerp Olympics, they fared poorly at the 8th Paris Olympics, with just one bronze medal in wrestling, won by NAITO Katsuya. Still, as facilities in Japan improved and Japanese athletes continued to interact with foreign athletes, the abilities of Japanese athletes improved to the point where they won three gold medals, two silver medals, and one bronze medal at the 9th Amsterdam Olympics in 1928.

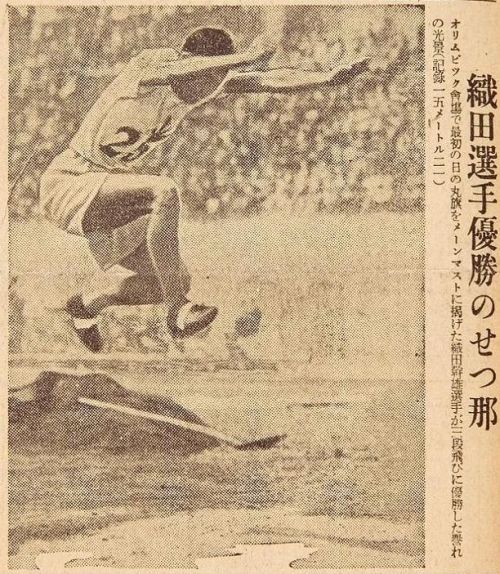

ODA Mikio, who had done no better than sixth place in the triple jump at the Paris competition, came close to equaling the world record of 15.41 m with a jump he made just before departing for Amsterdam. Tuulos from Finland and Peters from Netherlands were the favorites, but Oda was confident that he could at least take the bronze. Neither Tuulos nor Peters performed as well as expected, however, and Oda won the event with a jump of 15.21 m, winning Japan its first ever gold medal.

The organizers had not anticipated a Japanese athlete winning a gold medal and did have a national flag ready for the medal ceremony. They borrowed a flag from Japanese fans, but it was several times larger than the flags of the nations that won the silver and bronze medals. What’s more, the Japanese national anthem was played from about halfway through and was over in no time at all.

After retiring from competition, Oda taught young athletes, wrote lots of books, and served as a general director of athletic sports at the Tokyo Olympics in 1964.

The Amsterdam Olympics were the first modern games to include track and field events for women, and HITOMI Kinue was there as the only Japanese woman to participate in those Games. The long jump was her specialty, but there was nothing scheduled in that event for women, so she entered the 100 m sprint, which she was also good at. After failing to make the 100-m finals, however, she decided on a whim to enter the 800-m race, a distance that she had never run before.

The 800-m finals featured nine women, and Hitomi took the silver medal in a close race with Lina Radke from Germany. Several of the competitors were reported to be completely exhausted at the end of this race, which lead the IOC to decide that women were too frail for long distance running, and women's Olympic running events were limited to 200 meters until the 17th Roma Olympics in 1960.

Hitomi actively coached young athletes, and in 1929 held what she called “[the] very first training camp for Japanese women” (Goal ni hairu (reach the goal), Hitomi Kinue, Isseisha, 1931. [606-202]) at Miyoshino athletic field in Nara Prefecture. The camp lasted two weeks and 15 athletes participated. She also held a training camp prior to the 3rd Women's World Games in an effort to develop Japan’s female athletes.

Hitomi was also actively involved in fund-raising to send athletes to the Women's World Games. She made 400,000 souvenir bags and sold subscriptions to young women throughout Japan starting at 10 sen* each. She traveled the country to lecture and to express her thanks for all the support. She also worked as a newspaper reporter for the Osaka Mainichi Shimbun, which kept her busy every day. She fell ill and died from overwork on August 2, 1931, at the age of 24.

*A sen is 1/100th of a yen.

2) Ed., Osaka Mainichi Shimbunsha, Oshu Kankoki (travels in Europe), Osaka Mainichi Shimbunsha, 1928. [578-199]

Oshu Kankoki describes a trip to Europe organized by the Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbunsha and the Osaka Mainichi Shimbunsha held during the Amsterdam Olympics.

In Chapter 5, entitled “Deep Emotions at the Olympics,” Oda winning his gold medal is described as follows: “We jumped to our feet and gave him a standing ovation. We were proud to be Japanese and brushed tears from our eyes when the Rising Sun was raised as we sang Kimigayo at the top of our lungs.”

During the women’s 800-m finals, Hitomi was in third place coming out of the fourth turn when she overtook Gentzel to claim second place. “She overtook the second-place runner cleanly at the fourth turn and ran straight ahead, as fast as she could to catch up with Radke 15 m away. It was an amazing spurt. She risked life and limb, running as hard as she could to get closer to Radke. That’s what I call the Japanese spirit!” Her desperate dash to the finish line brought her within a hair’s width of the gold, but ultimately she finished with the silver.

The 10th Los Angeles Olympics in 1932

The success of Japanese athletes at the 9th Amsterdam Olympics together with the start of a movement to host the Olympic Games in Japan, prompted the Japanese media to begin to take a major interest in the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics. Although only a few reporters had been sent to cover the Amsterdam Olympics, a great many were in Los Angeles to cover the 10th Olympic Games.

Similarly, although the Japanese Olympic team in Amsterdam had only 43 athletes, 131 Japanese athletes participated in the Los Angeles Olympics. The financial difficulties that had plagued the athletes until then all but disappeared as the Government allocated 100,000 yen (currently, about 150 million yen) and Olympics support groups collected more than 200,000 yen from the public.

Japanese athletes won gold medals in five out of six men’s swimming events, and Nanbu Chuhei won in the triple jump. In all, the Japanese team won seven gold medals, seven silver medals, and four bronze medals.

3) Ed., Kobunsha, Olympics gaho dai 10 kai (10th Olympics illustrated), Kobunsha, 1932 [628-28]

The first half of Olympics gaho dai 10 kai comprises pictures of successful athletes, while the second half contains the results of various sporting events.

A chapter entitled “The Glory of Japanese Equestrians” describes how First Lieutenant Nishi Takeichi won a gold medal in Equestrian for individual show jumping and goes on to say “Japan has long been the laughing stock of the equestrian community but now has renewed prestige thanks to Nishi’s memorable performance.” In those days, this event was called “prix de nations” and staged just before the closing ceremony on the final day. It was considered a highly prestigious event and the nation that won it was regarded as a true Olympic champion. The course for the 10th Olympic Games was unusually challenging and many participants were disqualified. Nishi, however, cleared all the obstacles in the course on his favorite horse, named Uranus, and earned himself “a bright crown of victory through which he introduced himself to the outside world as young Baron Nishi.

Next

Chapter 2: Tokyo’s bid to host

the Olympics