- Kaleidoscope of Books

- The Senrigan Affair and Its Time Period

- The scholars’ views

The scholar’s views

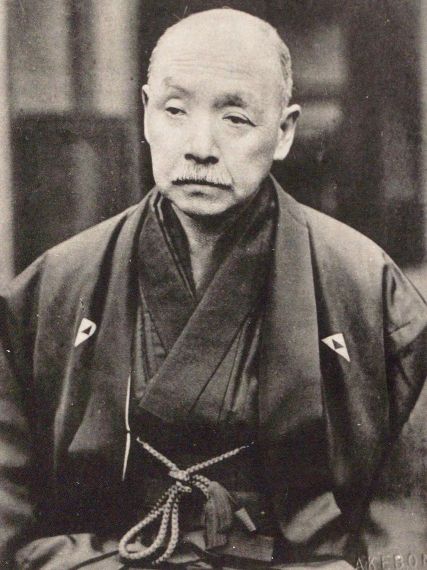

Anezaki Masaharu (1873-1949)

He was a religious scholar and critic. His pen name was “嘲風 (Chofu).” He was born in Kyoto. He graduated from the Department of Philosophy, College of Letters, Imperial University. He studied religious studies in graduate school. In 1898, he became a lecturer at the Imperial University's College of Letters. He became a professor in 1904, and in 1905 founded the Course of Religious Studies. He was invited to Harvard University to teach the Japanese civilization course from 1913 to 1915, and he was also active overseas. In 1928, he was awarded the Legion of Honour by the French government. He wrote “宗教学概論 (Shukyogaku Gairon)” (Introduction to religious studies) (1900), “切支丹宗門の迫害と潜伏 (Kirishitan Shumon No Hakugai To Sempuku)” (Persecution and Hiding of the Christian Sect) (1925).

Participation in the experiment

He participated in the third public experiment.

View

In the newspaper that reported on the third public experiment, it is said “When Dr. Inoue said ‘Since we had the result 道徳天..., we cannot say that vision is irrelevant. If unification is achieved, it will be 無我一念 (Muga Ichinen of so-called Buddhism). So, metaphysically...’, from somewhere, someone said ‘That is self-centered’ —Dr. Chofu Anezaki, who faced Dr. Inoue, smiled silently and calmly—” (“Juyon Hakase No Kyotan”, Tokyo Asahi Shimbun, 1910. 9. 18, Morning Ed., p.5. [Z81-1]), but his view is unclear.

Portrait Source

Ed., Chofu Kai, Anezaki Masaharu Sensei Shosi, Chofu Kai, 1935 [684-89]

Ishikawa Chiyomatsu (1860-1935)

He was a zoologist and enlightener of the theory of evolution. He was born in Edo. He studied at a foreign language school, Kaisei Preparatory School, and Tokyo University's Department of Biology. After graduating, he became an assistant professor at the same university. He studied in Germany from 1885 and studied under August Weismann. He taught zoology as a professor at the Imperial University's College of Agriculture since 1890. He served as Director of the Tokyo Imperial Household Museum and a member of the Imperial Academy. He summarized the lecture notes of his mentor, Morse, as “動物進化論 (Dobutsu Shinkaron)” (Animal Evolution). He wrote “進化新論 (Shinka Shinron)” (The new theory of evolution) (1891), “動物学講義 (Doubutsugaku Kougi)” (Lectures on zoology) (1913), etc.

Participation in the experiment

He did not participate in any experiments.

View

(Introducing the ecology of horse-tailed wasp, "Clairvoyance is usually thought of as a godlike act by humans, but I don't think it's at all mysterious. As I have said before, the action of the five senses that animals and insects have, as far back as the primitive age goes, humans also had them. Therefore, it seems to me that in ancient times, people were able to see through the bark of trees.” (Ishikawa Chiyomatsu, Shonen Rika; Fushigi Na Doubutsu No Gokan To Senrigan, Shonen Kurabu, 6(5), 1919.4. [Z32-387])

Portrait Source

Ed., Isikawa Chiyomatsu Zenshu Kankokai, Isikawa Chiyomatsu Zenshu, vol.1, Kobunsha, 1935. [693-62]

Inoue Tetsujiro (1856-1944)

He was a philosopher. He graduated from the Department of Philosophy at Tokyo University in 1880. He became an assistant professor at the University of Tokyo in 1882. In the same year, he co-authored “新体詩抄 (Shintaishi Sho)” (1882). He became a pioneer of the Shintaishi movement. He went on to study in Germany in 1884. After returning to Japan in 1890, he was appointed professor and taught German idealism until his retirement in 1923. He also rejected Christianity from a nationalist standpoint and advocated national morality, and in his later years he devoted himself to the study of Japanese Confucianism.

Participation in the experiment

He participated in the first and third public experiments and the Marugame experiment.

View

He was one of the instructors of Fukurai, who entered the Department of Philosophy at the College of Letters, Tokyo Imperial University in 1896, and wrote a preface to Fukurai's book, “催眠心理学 (Saimin Shinrigaku)” (Hypnotic Psychology) (1906). He not only participated in the first and third public experiments, but also went to Marugame to inspect the Nagao residence himself, taking a keen interest in the Senrigan affair. He also spoke actively in the media and was generally positive about clairvoyance and thoughtography. Inoue had a strong tendency to view clairvoyance not as a physical phenomenon, but as a matter of ethics and philosophy, and his views were criticized by physicists and Kato Hiroyuki. To quote Inoue himself, he said (after pointing out the need for research), “Some research may not be possible from the purely chemical or physical side. The scope of the project is different. I don't know if these methods of experiment are useless or not. In fact, this is something that, from the perspective of philosophy, psychology, or religion, has to do with solving various serious problems.” It is also interesting that he noted the practical applications of clairvoyance, such as the discovery of lost objects, missing persons, fugitive criminals, mineral veins, sunken ships, and marine resources, and its use in warfare. (Inoue Tetsujiro, Marugame No Senrigan Fujin Nagao Ikuko Ni Tsuite, Toa No Hikari, 6 (2), 1911.2. [雑55-26])

Portrait Source

National Diet Library Digital Exhibition, Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures

Imamura Shinkichi (1874-1946)

He was a psychiatrist. He was born in Ishikawa Prefecture, and graduated from Imperial University. He went on to study in Vienna in 1900. After returning to Japan, he became a professor at the College of Medicine of Kyoto Imperial University in 1903. He founded the Class of Psychiatry to study delusional disorders and neurosis. His posthumous book is “精神病理学論稿 (Seishin Byorigaku Ronko)” (Papers on Psychopathology) (1948).

Participation in the experiment

He collaborated with Fukurai in the experiments, and participated in the first and third public experiments, and the Marugame experiment. After that, he participated in other experiments at various locations.

View

In a lecture at the Kyoto Association of Medical Sciences, Imamura, who started clairvoyance experiments at the same time as Fukurai and was convinced of its existence, made the following remarks. He said that the existence of this clairvoyance ability is a believable fact and that clairvoyance is a kind of special sensory image which can be recognized as material reality. He went on to say that this kind of ability could exist in the normal mental life of a normal person, but it would be hidden by other distinct senses and would be unknown because it would not reach a level of clarity that would allow it to rise to the forefront of consciousness. (Imamura Shinkichi, Token Ni Tsuite, Kyoto Igaku Zasshi, 7 (2), 1910.4. [雑28-29])

Portrait Source

Ed., Kyoto Teikoku Daigaku Igakubu Seishimbyogaku Kyoshitsu, Imamura Kyoju Kanreki Syukuga Kinen Rombun Shu, Kyoto Teikoku Daigaku Igakubu Seishimbyogaku Kyoshitsu, 1936. [53-386]

Irisawa Tetsukichi (1865-1938)

He was an internal medicine specialist and historian of medicine. He was born in Echigo Province (Niigata Prefecture). In 1889, he graduated from the College of Medicine of the Imperial University and became an assistant to Erwin von Bälz. The following year, in 1890, he went to Germany to study. He returned to Japan in 1894. He became a professor of internal medicine at the College of Medicine of Tokyo Imperial University in 1901. He served as the Dean of the College of Medicine of Tokyo Imperial University, the Imperial Household Ministry's official physician, the head of the Taisho Emperor's court physicians, the President of the Japanese Society of Internal Medicine, the President of the Japanese Society for the History of Medicine, and the President of the Japanese Association of Medical Sciences. He contributed to a variety of fields, including beriberi and parasitic diseases.

Participation in the experiment

He participated in the first and third public experiments.

View

During the third open experiment, Chizuko had a stomach ache and was not feeling well, so she was examined by Irisawa after the experiment was over. Except for being a little deaf and suffering from conjunctivitis as a result of the after-effects of trachoma, he said “from the standpoint of physique, Chizuko doesn't show the slightest sign of abnormality.” Regarding the fact that Chizuko used clairvoyance to diagnose illnesses, he said, as a doctor, “The difference between clairvoyance and diagnosis of illness is completely distinct, so it is impossible to say that clairvoyance can be used to cure illness or to treat it. Although clairvoyance can reveal the extent of enlargement of the liver, there is no way to know whether a person will die or live because of enlargement of the liver.” (Toshi No Jikken To Sho Hakase, Kokoro No Tomo, 6(10), 1910.10. [雑5-21イ])

Portrait Source

Ed., Miyakawa Yoneji, Irisawa Tatsukichi Sensei Nempu, Irisawa Naika Dousoukai, 1940.11 [GK61-37]

Osawa Kenji (1852-1927)

He was a physiologist. He was born in Mikawa Province (Aichi Prefecture). In 1866, he moved to Edo and entered the Institute of Medicine. He went on to study in Germany in 1870. He returned to Japan in 1874, but returned to study in Germany in 1878. After returning to Japan again in 1882, he became a professor at the College of Medicine of Tokyo University. He became president of the College of Medicine of Imperial University in 1890. He was a member of the Imperial Academy. He built the foundation of modern physiology in Japan.

Participation in the experiment

He participated in the first and third public experiments.

View

“I think it would be a good idea to have her look through the human body, there are things such as x-rays and cystoscopes which physicians understand as well, and I think they would be the least likely to raise doubts about these methods, so I have recommended it.” (“Mienu Mono Wo Tokakusuru Sukoburu Mezurana Onnna No Jikken”, Asahi Shimbun (Tokyo), September 15, 1910, Morning Edition, p. 5. [Z81-1])

Portrait Source

Osawa Kenji, Reisuiyoku To Reisuimasatsu, Bunseido [and others], 1911.7. [61-102]

Oka Asajiro (1868-1944)

He was a zoologist and enlightener of the theory of evolution. He was born in Totomi Province (Shizuoka Prefecture). He studied at the Imperial University as a non-regular student. He went to Germany in 1891 to study under August Weismann, Rudolf Leuckart and others. He became a professor at Yamaguchi High School in 1895 and at Higher Normal School in 1897. He studied the development and morphology of ascidians and bryozoans, and made efforts to enlighten people on the theory of biological evolution. He made vigorous criticism of civilization and was a member of the Imperial Academy. He wrote “進化論講話 (Shinkaron Kowa)” (Evolutionary Discourse) (1904), “生物学講話 (Seibutsugaku Kowa)” (The Biological Discourse) (1916), and “猿の群れから共和国まで (Saru No Mure Kara Kyowakoku Made)” (From Ape Troop to Republic) (1926).

Participation in the experiment

He participated in the first and third public experiments.

View

“There are many things that can be said to be somewhat understandable from a biological point of view that are incomprehensible in other disciplines. One example is the clairvoyance that was reported in the newspapers recently.” “In the biological world, such things can be done, and the reason why ordinary people cannot do these things is because they don't have a special need for them, so they don't develop the ability” (Oka Asajiro, Seibutsugakuteki No Mikata, Toa No Hikari, 6(1), 1911.1. [雑55-26]). He said, “I have even confirmed something similar to this in the case of the Uma No O Bachi as a result of my research. I wondered if the so-called ‘Senrigan’ could be similar to these abilities. However, while Chizuko was experimenting in the Ohashi residence, I found a very suspicious case,” and referred to the changing of the lead pipe. “However, since she was a woman, they could only allow Chizuko take credit, at this time especially.” (Senrigan No Umu, Gurahikku, 3(4), 1911. 2. [雑53-13])

Portrait Source

Lectures by Oka Asajiro, Ed., Gyotei Kikuchi, Jinrui Shinka No Kenkyu, Daigakukan, 1915. [360-124イ]

Katayama Kunika (1855-1931)

He was a forensic doctor. He was born in Totomi Province (Shizuoka Prefecture). He graduated from the College of Medicine of Tokyo University in 1879. He became an assistant professor at Tokyo University in 1881. In 1884, he went to Europe to study forensic medicine. After returning to Japan in 1888, he became a professor at the Imperial University's College of Medicine. He established the first department of forensic medicine in Japan in 1889, and in 1897 he taught in the department of psychiatry as well. He served as Director of Sugamo Hospital in Tokyo and Professor of Medicine at the Naval Medical School. In his later years, he worked for the temperance movement. His publications include “最新法医学講義 (Saishin Hoigaku Kogi)” (The Latest Forensic Lectures) (1900).

Participation in the experiment

He participated in the first and third public experiments.

View

His comments were not particularly conveyed.

Portrait Source

Ed., Tokyo Teikoku Daigaku Igakubu Hoigaku Kyoshitsu 53 Nenshi Hensankai, Tokyo Teikoku Daigaku Hoigaku Kyoshitsu 53 Nenshi, Tokyo Teikoku Daigaku Igakubu Hoigaku Kyoshitsu, 1943. [60-1809]

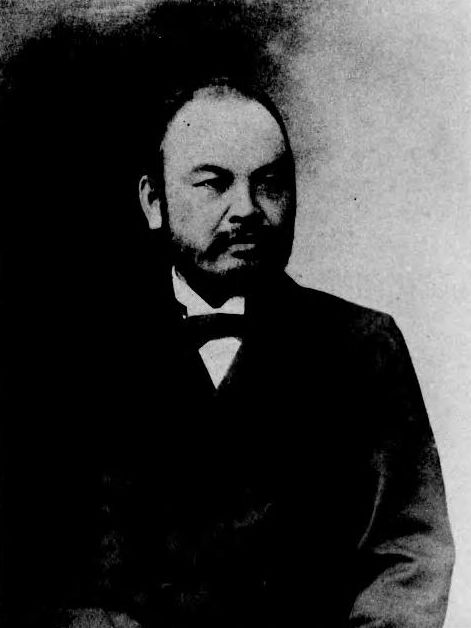

Kato Hiroyuki (1836-1916)

He was a political scientist. His father was a samurai from the Izushi Clan. He studied Rangaku (western studies) under Sakuma Shozan and Oki Nakamasu (later Tsuboi Ishun). He became an assistant professor at Bansho Shirabesho (Institute for the Study of Barbarian Books) and studied German studies. After the Meiji Restoration, he served in the government and served as the Senior Secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In 1877, he was appointed as President of the Faculty of Law, Science and Literature at the Tokyo Imperial University, and in 1891, the President of the same University. He served as a member of the Chamber of Elders and President of the Imperial University, was elected to the House of Peers in 1890 by imperial order, and received the title of baron in 1900. President of the Imperial Academy and Privy Councillor. He wrote “真政大意 (Shinsei Taii)” (1870) and “国体新論 (Kokutai Shinron)” (1874) in the first half of his career, and “人権新説 (Jinken Shinsetsu)” (1882) in the latter half of his career, after turning from the theory of natural rights to the theory of social evolution.

Participation in the experiment

He did not participate in any experiments.

View

(In a critique of Inoue Tetsujiro's lecture, “哲學上より見たる進化論 (Tetsugaku Jou Yori Mitaru Shinkaron)” (Evolutionary theory as seen from philosophy)), “I have heard that various theories have appeared among scholars about the so-called Senrigan and clairvoyance recently, and among them, those such as Dr. Inoue's have stated that this is indeed a philosophical or religious problem and that no research can be conducted based on the natural sciences. If this is the case, we must study the mysterious, mystical and supernatural realm of static reality, but I cannot do this. This unusual phenomenon, which I know nothing of of, but which is similar to what is called ‘atavism’ (“reappearance” or “reconstruction”), I conjecture it is a reappearance of eyesight from the time of our ancestors in the age of animals, but as this is nothing more than conjecture, I will never assert it, but in any case, such a thing as this should never be studied only in the human world, and it will never be understood unless it is studied all the way to the animal world.” (Kato Hiroyuki, Shinkagaku Yori Mitaru Tetsugaku, Tetsugaku Zasshi, 25(285), 1910.11. [Z9-253])

Portrait Source

National Diet Library Digital Exhibition, Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures

Kinoshita Hiroji (1851-1910)

He was a jurist. He was born in Higo Province (Kumamoto Prefecture). Born into a family of Confucian scholars in the Kumamoto Domain, he studied in France after graduating from the Daigaku Nanko and the Ministry of Justice's Meiho Ryo. He graduated from the University of Paris in 1879. After serving as a professor at the University of Tokyo, president of the First Higher Middle School, and director general of the Ministry of Education, he became the first president of Kyoto Imperial University in 1897. He was also a member of the House of Peers.

Participation in the experiment

He didn’t participate in any experiments.

View

In August 1909, while recuperating from an illness, he received treatment for Chizuko. In doing so, he let her see through an enclosed business card. Before the meeting, he gave his business card to Chizuko, who was in Osaka, and she guessed his age, appearance, and medical condition, so he said, "I must call it strange”. He recommended Chizuko's research to Professor Imamura at the medical school. The treatment itself was only a stroking of the affected area, and "we did not see a significant effect on the sick". He died in August of the following year.

Portrait Source

Ed., Oosaka Asahi Shimbunsha, Jimbutsu Gaden, Yurakusha, 1907.7. [76-244]

Kure Shuzo (1865-1932)

He was a psychiatrist and medical historian. He was born in Edo. In 1890, he graduated from the Imperial University Medical College and entered the Department of Psychopathology. In 1897, he went to Europe to study under Emil Kraepelin and others. After returning to Japan in 1901, he became a professor at the College of Medicine of Tokyo Imperial University. He was the director of Sugamo Hospital in Tokyo. He criticized the Act on the Custody of the Psychotic, which condoned the use of jail cells for people with mental illnesses, in his book, “精神病者私宅監置ノ実況及ビ其統計的観察 (Seishimbyosha Shitaku Kanchi No Jikkyo Oyobi Sono Tokeiteki Kansatsu)” (Real Situations of Private Custody of the Mentally Ill Patients and its Statistical Observation), co-authored with Goro Kashida (1918). His books in the field of medical history include “シーボルト先生其生涯及其功業 (Siboruto Sensei Sono Shougai Oyobi Sono Kogyo)” (The Life and Works of Dr. Siebold) (1826).

Participation in the experiment

He participated in the first and third public experiments.

View

“There are people who are so sickly hysterical that their minds are so full of energy that they can see even the most trivial things. In addition, Senrigan users sometime fall into a hypnotic state and the mind is outside the normal situation, and in this case it is not necessarily impossible to perform clairvoyance due to the action of the moment, but today's Senrigan is still not good enough.” (Senrigan No Umu, Gurahikku, 3(4), 1911.2. [雑53-13]) (Criticizing Chizuko and Ikuko for putting conditions on experimental objects and rooms), “I can't be sure of the abilities at all. It is impossible to measure how far a person's brain power will develop, and one might say that clairvoyance is due to an abnormality in brain power, but there is a sequence of brain power development and there is a hierarchy. Today, there is no reason why brain power could be so far above the level of ordinary human brain power that it suddenly becomes Senrigan. A steamer of tens of thousands of tons can't suddenly be built from a canoe.” (Kure Shuzo, Marukibune Kara Issokutobini Daikisen Ha Dekinai, Jitugyo Shonen, 5(2), 1911.2. [Z32-B247])

Portrait Source

Ed., Kure Kyoju Rishoku 25 Nen Shukugakai, Kure Kyoju Rishoku 25 Nen Kinen Bunshu, Kure Kyoju Rishoku 25 Nen Shukugakai, 1928. [493.7-Ku59ウ]

Goto Makita (1853-1930)

He was a pioneer of science education. He was born in Mikawa Province (Aichi Prefecture). He studied at Keio University and participated in the establishment of the Junior High School Normal Course of Tokyo Normal School in 1876, after which he was a professor there. Advocating the importance of experiments in science and chemistry education, he devised simple experimental equipment. He was known as an avid advocator of romanization of Japanese writing.

Participation in the experiment

He participated in the third public experiment.

View

He pointed out that Chizuko allowed only gluing or paper string and no sealing or soldering of experimental objects. He said, “I opened this seal and tried to see how long it would take to put it back on. I made a piece of Japanese paper, one inch and a half wide, with adhesive paste at a depth of four inches on the edge, and dried it and stamped it with red ink on the border between the paper and the board. It took forty-two seconds to peel off the paper by wetting it with spit, and one and a half minutes to set the seal together, and four minutes to dry it on the skin, for about six and a half minutes in total.” He expressed his skepticism, “Such a sealing method cannot be used to verify Chizuko's ability, as it is not an actual experiment.” (Goto Makita, Senrigan Fujin No Jikken Ni Tsuite, Toyo Gakugei Zasshi, 27(350), 1910.11. [雑55-24]) Incidentally, given that Chizuko did not show her hands when performing clairvoyance, that it took her several minutes to perform, and that most of the experiments that she succeeded in seeing through the object were made with glue seals, Goto's points can be said to be a strong basis for skepticism.

Portrait Source

Ed., Mita Shogyo Kenkyu Kai, Keio Gijuku Shusshin Meiryu Retsuden, Jitugyo No Sekaisha, 1909.6. [39-113]

Tanakadate Aikitsu (1856-1952)

He was a physicist. He graduated from the College of Science at the University of Tokyo in 1882. After studying in England and Germany, he became a professor at the College of Science of the Imperial University, and a Doctor of Science, in 1891. He measured gravity and geomagnetism throughout Japan, and in 1899 he established a Latitude Observatory in Mizusawa, Iwate Prefecture. He also studied aeronautics, and worked to popularize the metric system and Japanese romaji. Member of the Imperial Academy in 1906 and member of the House of Peers in 1925. He was awarded the Order of Culture (Geophysics and Aeronautics) in 1944.

Participation in the experiment

He participated in the first and third public experiments.

View

Along with Yamakawa, he was a leading physicist. “The center of the conversation was, of course, the famous Dr. Tanakadate. He was sitting in the center of the doctors, stroking his sandwich beard with a salt and pepper, square cut, while he was discussing with Dr. Yamakawa, who was stationed at his right hand with his gold-rimmed glasses shining: ‘It's a brilliant success, but in fact, what can be called science doesn't allow confirmation from just one time. I'm not going to doubt it, but I'd like to see it one more time. If I roll two dice and she guesses what I hide, I'll be satisfied with that.’ When he said that, he was smiling behind the doctors.” (“Juyon Hakase No Kyotan”, Asahi Shimbun (Tokyo), 1910.9.18, Morning Edition, p. 5. [Z81-1]) The dice experiment described by Tanakadate at this time was later carried out by Fukurai.

Portrait Source

National Diet Library Digital Exhibition, Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures

Tamaru Takuro (1872-1932)

He was a physicist and advocator of romanization. He was born in Iwate Prefecture. Graduated from First Higher School and the Tokyo Imperial University College of Science Department of Physics. After working as an assistant professor at Kyoto Imperial University, he became an assistant professor at Tokyo Imperial University in 1900. He studied in Germany from 1902 to 1905. He became a professor in 1907. He established the Japanese Romaji Association with Tanakadate and others and advocated a Japanese spelling style as opposed to the Hepburn style. His writings include “ローマ字国字論 (Romaji Kokujiron” (The Romanized Official Script) (1932).

Participation in the experiment

He didn’t participate in any experiments.

View

(Stating that it's troubling when newspapers report something as unsure as Senrigan), “In short, even though this was a problem that could not be studied scientifically, it was extremely embarrassing because of the blurbs in the newspapers and by psychologists that if it was not studied, it would have a negative impact on the public's confidence.” (Tamaru Takuro, “Hasigaki”, included in Fuji Kyotoku, Fujiwara Sakuhei, Senrigan Jikkenroku, Dainihon Tosho, 1911.2. [327-420])

Portrait Source

Tamaru Takuro, Romaji Kokujiron, Iwanami Shoten, 1932. [811.8-Ta656r2]

Nagaoka Hantaro (1865-1950)

He was a physicist. He was born in Nagasaki Prefecture. In 1887, he graduated from the Department of Physics at the Imperial University's College of Science. He became an assistant professor in 1890. He studied in Germany from 1893 and became a professor in 1896, and trained many physicists until his retirement in 1926. In 1917, he was involved in the founding of the Institute of Physical and Chemical Research and directed the Nagaoka Laboratory, where he made achievements in atomic physics. In 1931, he became the first president of Osaka Imperial University. He served as President of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and President of the Imperial Academy. Cultural Merit. In 1937, he was awarded the first Order of Cultural Merit.

Participation in the experiment

He didn’t participate in any experiments.

View

On April 25, 1910, at a special meeting on psychology, he heard Fukurai’s report on a business trip to Kumamoto and commented, “The reason she was able to read the letters on her business card was that there was a kind of ray coming out of the carbon. The reason why she couldn't read the letters in the double box that Mr. Imamura carried was because the black letters were wrapped in black velvet and the rays from the letters got confused with the rays of the black cloth. If so, letters written in red should not be able to be read.” In response to this, Fukurai performed a correspondence experiment on Chizuko, and the result was a success in any color of letters. (Fukurai, Toshi to Nensha)

Portrait Source

Okaya Tatsuji, “Nagaoka Hantaro Hakase”, included in Ed., Jinbunkaku, Kindai Nihon No Kagakusha 3, Jinbunkaku, 1942. [769-183]

Nakamura Seiji (1869-1960)

He was a physicist. He was born in Echizen Province (Fukui Prefecture). In 1892, he graduated from the Department of Physics of the Imperial University College of Science. He became an assistant professor in 1900. After studying in Germany and France from 1903 to 1906, he became a professor in 1911. He was a member of the Imperial Academy. Cultural Merit. Conducted a geomagnetic and geodetic survey in cooperation with the Tanakadate. Instructed students to conduct fire investigations during the Great Kanto Earthquake. His research focused on the application of physics to lighting, architectural acoustics, and the preservation of antiquities. His writings include “物理学実験法 (Butsurigaku Jikkenho” (Experimental Methods in Physics) (1934).

Participation in the experiment

He didn’t participate in any experiments.

View

He published a dialogue with Fukurai in “東洋学芸雑誌 (Toyo Gakugei Zasshi)” (Oriental Studies Magazine), 28(356), 28(357), 28(358). [雑55-24]), contributed a preface to Fuji and Fujiwara's Senrigan Jikkenroku, and made numerous statements about the Senrigan affair. On March 21, 1911, after giving a lecture at Tokyo Imperial University, he performed a senrigan magic trick. In his speech, he discussed both the pros and cons of the idea, and stated his own argument against clairvoyance. “Is there a theory of clairvoyance in the first place? People said that this was what hypnosis was all about. Dr. Inoue also said that there was a connection between hypnosis and clairvoyance. He asked how one could get to know if he put an experiment in front of a hypnotized person.” (Nakamura Seiji, Ichi Rigakusha No Mitaru Senrigan Mondai, Kaitakusha, 6(4), 1911.4. [Z190.5-Ka1] and Nakamura Seiji, “Senrigan No Tejinashi Toshiteno Watashi No Taiken”, Butsurigaku Shuhen, Kawade Shobo, 1938. [46-452])

Portrait Source

Lecture by Nakamura Seiji, Ed., Tomioka Masashige, Renzu Shusa Ron, Munataka Shobo, 1957. [425.91-N421r-T]

Fuji Kyotoku (?-1923)

He was a physicist. Born in Osaka. In 1908, he became a lecturer at Tokyo Imperial University's College of Science. He was promoted to professor in March 1923, but died the same month. He studied electric fish (Shibire Ei), etc.

Participation in the experiment

He participated in experiments in Marugame.

View

He traveled to Marugame to conduct Ikuko's experiments with Yamakawa and Fujiwara. During a thoughtography experiment, he lost a dry plate. He and Fujiwara co-authored the book “千里眼実験録 (Senrigan Jikkenroku).” Because he was the most adamant in his denial of the clairvoyant, he was a target of the clairvoyant's followers. “Before I went to Marugame, I had been suspicious of Mrs. Ikuko’s thoughtography... In short, from what I've been investigating, I've found that there were a lot of causes for suspicion about her thoughtography, and a lot of room for suspicion if you suspect that she was using magic tricks.” (Fuji Kyotoku, “Kenkyu No Kachi Wo Mitomezu”, Jitsugyo Shonen, 5(2), 1911.2. [Z32-B247])

Fujiwara Sakuhei (1884-1950)

He was a meteorologist. After graduating from the Department of Theoretical Physics at Tokyo Imperial University in 1909, he joined the Central Meteorological Observatory. In 1920, he was awarded the Imperial Academy Prize for his work on the anomalous propagation of sound. In the same year, he began studying in Europe. He became a professor at Tokyo Imperial University in 1924. In 1941, he became director of the Central Meteorological Observatory and oversaw wartime meteorological operations. He made achievements in vortex research. He was also engaged in enlightenment and known as “Dr. Weather”.

Participation in the experiment

The experiment in Marugame.

View

He and Fuji co-authored the book Senrigan Jikkenroku. In his later years, he had little to say about the Senrigan experiments, but one night, he was said to have talked to Wadachi Kiyo'o, a junior at the meteorological observatory who served as the first director of the Japan Meteorological Agency. (Wadachi Kiyoo, “Nensha Fujin—Marugame Senrigan Jikken Temmatsu”, Kokoro, 26(3), 1973.3. [Z23-48])

Portrait Source

Okada Takematsu, “Fujiwara Sakuhei Hakase”, Kagaku, 20(12), 1950.12. [Z14-72]

Matsumoto Matataro (1865-1943)

He was a psychologist. He was born in Kozuke Province (Gunma Prefecture). After graduating from Tokyo Imperial University, he went on to graduate school to study under Motora Yujiro. After studying at Yale University in the United States, he moved to Germany to study under Wundt. After returning to Japan, he worked as a lecturer at Tokyo Imperial University, where he was instrumental in establishing the psychology laboratory run by Motora. He became a professor at Kyoto Imperial University in 1905. In 1913, he became a professor at Tokyo Imperial University following the sudden death of Motora. He was the first president of the Japanese Psychological Association. He strived to apply psychology in a variety of ways.

Participation in the experiment

He didn’t participate in any experiments.

View

Matsumoto was a supervisor of 三浦恒助 (possibly Tsunesuke Miura, pronunciation of his name is unknown), who was the one who made the name “Kyodai Kosen,” and is believed to have provided guidance and advice for Miura's experiments. However, he has been shown to be skeptical of the results of the experiment, having said, “Mr. Miura, a student of the College of Letters at Kyoto University is experimenting on Ikuko, and he is very interested in clairvoyance, so he went to Marugame with various materials in consultation with people from the College of Science and Engineering for research. The results of the experiment have not yet been determined,” “Kyodai Kosen? It is not named Kyodai Kosen yet. It was written in his letter that Miura said it was enough to name it Kyodai Kosen at present, and unexpectedly it became popular,” “Although photographic sensitization is a curious phenomenon, I have doubts whether the darkroom in which the experiment was conducted was perfect or not.” (“Matsumoto Hakase No Iken”, Asahi Shimbun (Tokyo), January 6, 1911, Morning Edition, p.3). Matsumoto became a professor at Tokyo Imperial University following Motora's death, and Fukurai, who had been an assistant professor, was put on leave (in a de facto “undesirable discharge”) from Tokyo Imperial University. According to Fukurai's biography, if all went well, the assistant professor Fukurai was expected to succeed Motora and be promoted to professor.

Portrait Source

Ed., Tanaka Kan-ichi, Kido Mantaro, Shinrigaku Shin Kenkyu, Iwanami Shoten, 1943. [140.4-Ta84-ウ]

三浦恒助 (pronunciation and birth/death date unknown)

He was a student at Kyoto Imperial University, College of Letters. He studied psychology under Matsumoto Mantaro. He went to Marugame to conduct experiments on Ikuko. His permanent address was said to be in Aichi Prefecture, but there are reports that he was from Marugame. In July 1911, he graduated from the College of Letters. He graduated from medical school in November 1916. His career after that is unknown.

Participation in the experiment

He participated in the experiment in Marugame. After that, he seemed to experiment with clairvoyance in various places.

View

Miura carried out experiments with the advice of doctors at medical and science colleges. In the paper that reported the results, he criticized Fukurai for trying to avoid physical experiments. “Doctor of Literature and assistant professor Tomokichi Fukurai explained that infinite mental possibility works actively at any opportunity, returning to the state of ālaya-vijñāna, or it is the mind’s eye, or it is one of the Abhijñā or it depends on the state of potential mental non-self ecstasy. Such an explanation would be very easy. However, although these would have been nice if it had been for religion or art, they have been of little use when looking at it as a field of study.” (三浦恒助, “Toshi No Jikkenteki Kenkyu”, Geibun, 2(1), 1911.1. [雑8-54]) And, although he thought that clairvoyance was due to the action of unknown rays of light which he named “Kyodai Kosen” and publicly announced, later he turned to denial about clairvoyance and said, “Even though it was only for a short time, once I believed this as a fact, I could be accused of being very foolish and thoughtless in telling newspaper reporters about it.” (三浦恒助, “Yo Ga Jikken Shitaru Iwayuru Senrigan”, Geibun, 2(4), 1911.4. [雑8-54])

Miyake Hiizu (1848-1938)

He was a medical scientist. He was born in Edo. In 1863, he accompanied a mission of the Shogunate to Europe. He taught at the Daigaku Toko (later the University of Tokyo's Faculty of Medicine) from 1870, served as Dean of the University of Tokyo's Faculty of Medicine, and became President of the Imperial University Medical College in 1886. He was instrumental in establishing medical education and the health care system. He became the first Japanese Doctor of Medicine. He served as a member of the House of Peers and in other positions.

Participation in the experiment

He participated in the first and third public experiments.

View

He participated in the third public experiment with his eldest son, Koichi, a psychiatrist and medical school professor. No comments in particularly have been conveyed.

Portrait Source

Miyake Hiizu, Eisei Chojuho, Fuzanbo, 1929. [61-377]

Motora Yujiro (1858-1912)

He was a psychologist. He was born in Harima Province (Hyogo Prefecture). After studying at Doshisha English School, he moved to Tokyo and helped to found Aoyama Gakuin. He went to the United States in 1883 and studied at Boston University and Johns Hopkins University. After returning to Japan in 1888, he taught psychophysics as a lecturer at the Imperial University's College of Letters. He became a professor in 1890. As the first psychologist in Japan, he worked to establish research in experimental psychology. His theories were summarized in a collection of posthumous works, “心理学概論 (Shinrigaku Gairon)” (Introduction to Psychology) (1915).

Participation in the experiment

He participated in the third public experiment.

View

As a graduate school supervisor, he encouraged Fukurai to study abnormal psychology. He said, “In contrast to the tendency in the West to try to solve this kind of problem by the power of precise science, in the East there is a tendency to push the problem away as a mystery, that is, in India, China, and Japan there is faith in divine power, heavenly eye power or mysterious power that has developed from ancient times, and this has the effect of inhibiting precise research on various things,” “It is doubtful whether this Senrigan woman, Chizuko Kiyohara, will be a valuable target for psychological research,” “I do not intend to study something unusual in the field of psychology, such as a Senrigan woman, but rather to study it from other real perspectives.” (“Toshi No Jikken To Sho Hakase”, Kokoro No Tomo, 6 (10), 1910.10. [雑5-21イ]) In his introduction to Toshi to Nensha, Fukurai mentioned that the reason for the delay in the publication of the book was that he was unable to reproduce the results of the experiment in front of other scholars, and that the psychic had died, and “A certain person that it was not possible for me to disobey the advice of told me that I might have to postpone the publication. ” It is assumed that this “certain person” was Motora, who died in the previous year.

Portrait Source

Motora Yujiro, Shinrigaku Gairon, Teibi Shuppansha [and others], 1915. [356-126]

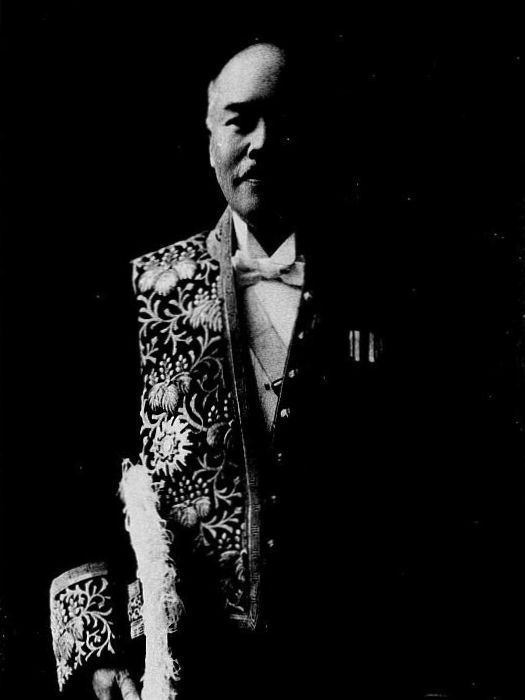

Yamakawa Kenjiro (1854-1931)

He was a physicist. His father was a samurai of the Aizu clan, and Yamakawa himself was a member of the Byakkotai. In 1871, he studied at the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale University. After returning to Japan, he worked as an assistant professor at the Tokyo Kaisei School and became the first Japanese professor of the Faculty of Science at the University of Tokyo in 1879, where he supported the early days of physics education by conducting follow-up experiments on X-ray generation. He became Japan's first Doctor of Science in 1888 and a member of the Tokyo Academy in 1901. In the same year, he became president of Tokyo Imperial University, but resigned in 1905 over measures to resolve the Shichi Hakase Kempaku Jiken (The Affair of the Opinions of Seven Doctors). He then served as president of Kyushu Imperial University before becoming president of Tokyo Imperial University again in 1913, and for 10 months from 1914 he also served as president of Kyoto Imperial University, where he devoted himself to educational administration. He was a member of the House of Peers in 1905. He became a Privy Councillor in 1923.

Participation in the experiment

He participated in the first and third public experiments and the experiment in Marugame.

View

As a leading figure in the world of physics, he set out to explain clairvoyance. In addition to preparing his own experimental object and conducting public experiments, for the experiments on Ikuko he himself went to Marugame to conduct thoughtography experiments with the cooperation of Fuji and Fujiwara. Yamakawa's interest in mysterious psychic effects and clairvoyance went back to his youth, and he once witnessed a clairvoyance experiment while he was studying in the United States. (Ed., Hanami Sakumi, Danshaku Yamakwa Sensei Den, Ko Danshaku Yamakawa Sensei Kinenkai, 1939. [289-Y27ウ]) In terms of clairvoyance research, he argued that it should be conducted from two perspectives: (1) whether it exists, and (2) the nature of the phenomenon (if it does exist). “It is possible that physiologists, psychologists, and philosophers may be more suitable than physical scientists for research from the second perspective, but I am convinced that psychologists should not be able to determine the presence or absence of facts from the first perspective, and instead physical scientists are the most appropriate.” (Source: The correspondence in Fuji and Fujiwara, Senrigan Jikkenroku.)

Portrait Source

National Diet Library Digital Exhibition, Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures

Next

References