- Kaleidoscope of Books

- The Senrigan Affair and Its Time Period

- Chapter 2: Reading about controversy among scholars

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Reading about the Senrigan Experiment

- Chapter 2: Reading about controversy among scholars

- Chapter 3: Reading about the Senrigan craze

- The scholars’ views

- References

- Japanese

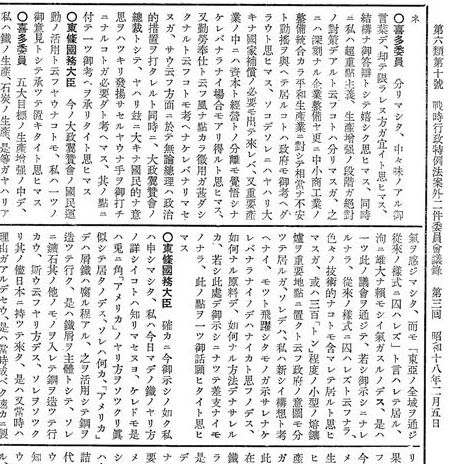

Chapter 2: Reading about controversy among scholars

In the Senrigan Affair, scholars from various disciplines took part in the experiment and presented their views to the media. The participants in the debate were the leading scholars of the time. In Chapter 2, we would like to follow the views of these scholars.

The study of clairvoyance was initiated by Fukurai Tomokichi, an assistant professor at Tokyo Imperial University's College of Letters, and Imamura Shinkichi, a professor at Kyoto Imperial University's College of Medicine. At that time, the Imperial University had a collegiate university system, and the College of Letters and the College of Medicine were equivalent to today's Faculties of Letters and Medicine. Clairvoyance was considered to be a problem related to human psychology or the psyche from the beginning, and scholars at the College of Letters (Tetsujiro Inoue, Yujiro Motora, and others), where psychology courses were taught, and the College of Medicine (Irisawa Tatsukichi, Kure Shuzo, and others), where psychiatry was studied, competed to express their views.

When clairvoyance and thoughtography became widely reported, physicists at the Tokyo Imperial University's College of Science (Yamakawa Kenjiro, Tanakadate Aikitsu, Nakamura Seiji, Fujiwara Sakuhei, and others) set out to explain them. They actively participated in experiments. Biologists from the College of Agriculture and other institutions (Ishikawa Chiyomatsu, Oka Asajiro etc.) also expressed their own views.

Tokyo Imperial University and Kyoto Imperial University

The Kyoto Imperial University was founded in 1897 as the second national university after the Tokyo Imperial University. At the time of its founding, the Colleges of Science and Technology were established, followed by the Colleges of Law and Medicine in 1899, and then the College of Letters in 1906, and the development of the university progressed as a comprehensive university. At the time of the Senrigan affair, College of Medicine professor Imamura Shinkichi collaborated with Fukurai in experiments, while 三浦恒助 (Miura Tsunesuke? Pronunciation of his name is unknown), a student majoring in psychology at the College of Letters, traveled to Marugame to conduct clairvoyance experiments on Ikuko. Miura believed that clairvoyance was due to the action of unknown rays of light, and named them "Kyodai Rays" after his alma mater. In his experimental report, he severely criticized Fukurai's view that clairvoyance was a mental action. Kyoto Imperial University had just been newly established, but it seemed to have developed a sense of rivalry with Tokyo Imperial University.

Physicists

Physicists, including former president of Tokyo Imperial University Yamakawa Kenjiro, attempted to test the physical aspects of clairvoyance and thoughtography in experiments. They did not necessarily approach their experiments with a negative attitude from the beginning, and devised methods of experimentation that did not exclude the possibility of the existence of clairvoyance and thoughtography. However, it is difficult to say that proper experiments could have been carried out at all because of the various requirements imposed by the psychics, and finally clairvoyance was denied in the book Senrigan JIkkenroku by Fuji Kyotoku and Fujiwara Sakuhei. In addition, the newspapers were initially critical of the physicists, defending Fukurai, but gradually became more negative about clairvoyance, probably due to the persuasive power of the physicists empirical work, as well as the exposure of the scandal.

Is Senrigan a mental action?

On the other hand, some scholars explained clairvoyance in terms of mental action, rather than physical phenomena. In the beginning, Fukurai himself thought it was a physical phenomenon and experimented with it as such, but he gradually came to explain it as a mental action. The philosopher Inoue Tetsujiro, one of Fukurai's mentors, postulated that we should think of clairvoyance as a metaphysical problem after a public experiment. The psychiatrist Kure Shuzo suggested that the mesmeric state makes the senses acute, and questioned the reasoning that clairvoyance is too far removed from normal mental action. He saw it as a problem of mental action and denied it as such.

Evolutionists

Although the clairvoyant experiment was severely criticized by physicists, a theory emerged to defend it from an unexpected place. Biologists gave an example of a wasp called Uma No O Bachi (horse-tailed wasp) laying its eggs by stinging parasitic insects in trees through the bark, which they attributed to clairvoyance. And if it was possible in the course of biological evolution, they thought it was not unnatural for such traits to appear in humans. Kato Hiroyuki, a political scientist and former president of the Tokyo Imperial University, also spoke about the case from the standpoint of evolutionary theory. At that time, there was a great deal of enlightenment about the theory of evolution from the standpoint of biology and the social sciences.

Retrospective of Nakaya Ukichiro

Nakaya Ukichiro (1900-1962), a physicist known for his research on snowflakes, wrote an essay during World War II in 1943 that recalled the Senrigan Affair more than 30 years ago (Nakaya Ukichiro, Senrigan Sonota, Bungei Shunju, 21(5), 1943.5. [Z23-10] ). If you read the “Appendix”, which was added after the war when the article was re-recorded in a book, you can see that similar pseudo-science affairs occurred many times after the Senrigan Affair.

5) Nakaya Ukichiro, “Senrigan Sonota”, Shunso Zakki, Seikatusha, 1947. [404.9-N44-5ウ]

Nakaya said of the pseudo-science incident, “An affair like that of Senrigan can occur independently of the progress of science in a country. It is an epidemic fever that emerges from the accumulation of manic and unconscious but inappropriate desires of the human mind. And in defense of that, science and most academics are rather helpless.” In “Appendix”, which he added after the war, Nakaya revealed that at the time of writing, “the great clairvoyance affair of the century between the cabinet, the navy, and the Pacific War was occurring, and I wrote this sentence in order to contain it somewhat.” The affair was that the chief of the materials department at the naval arsenal jumped at the invention of “piling up iron sand in a field, adding aluminum powder to it, and setting it on fire, so that the iron sand could be turned into pure iron at once,” and the cabinet almost adopted it as a national policy. Although this method of steelmaking is possible, it is completely impractical because it consumes a large amount of aluminum, which is much more expensive than iron. Followers of this method advocated a theory that underestimated the consumption of aluminum against the law of conservation of energy, which eventually led to the topic making an appearance in Prime Minister Tojo's answers in the House of Representatives. If you read the account of this affair in “Appendix,” the role of the scientists that Nakaya describes in the main part becomes convincing. Nakaya studied physics from Terada Torahiko during his time at Tokyo Imperial University and, like his teacher, was known as an outstanding essayist.

Next

Chapter 3