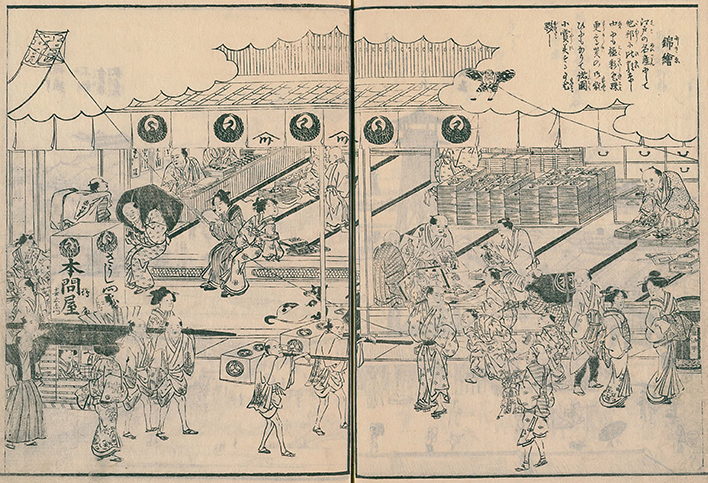

Production and sale of nishiki-e (brocade pictures)

Nishiki-e (brocade picture) (Edo book store (Tsuruya Kiemon) storefront)

Edo Meisho Zue ![]() by Saito Choshu, et al. <839-57>

by Saito Choshu, et al. <839-57>

"Nishiki-e are by far the most famous products of Edo in other countries. The playful use of colors in particular, is greatly admired in many countries."

The Edo Meisho Zue (Guide to famous Edo sites) has descriptions like the above, showing that nishiki-e were not only loved by the common people of Edo, but were also popular with nobles and in the countryside.

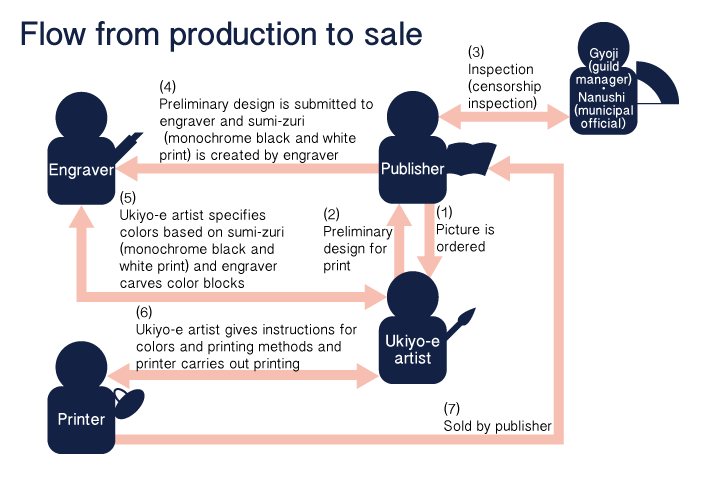

The pictures became able to be provided in large quantities at low prices, even as souvenirs, after a production system was established by painters, publishers, engravers and printers.

Publishers were e-zoshi-ya (stores which sell illustrated story books) and jihon toiya (publishers and sellers that dealt with entertaining publications), which fulfilled the roles of modern day publishing companies and producers. The publishers established a plan, and ordered a picture from a painter. Or in some cases, a painter would bring a picture to a publisher. (Figure 1) A painter creates a preliminary design for a print based on an order from a publisher. At this stage, the preliminary design for the print is still a black outline with no other colors. (Figure 2) The preliminary design for the print is then submitted for inspection (censorship inspection) through the publisher. (Figure 3) The ukiyo-e (pictures of the floating world) inspection system was started as part of the Kansei Reforms (1787-93) and from 1791 the nishiki-e came to be marked with an aratame-in (censorship seal) to show that they had undergone inspection. At first, the inspections were carried out by gyoji (guild managers) selected by the jihon toiya nakama (guilds of publisher-booksellers), however after the jihon toiya nakama were discontinued with the Tenpo Reforms (1830-44), the inspections came to be carried out by e-zohi-kakari-nanushi (municipal officials in charge of publishing).

Preliminary designs for prints which passed inspection were then delivered to an engraver. The engraver would paste the preliminary design for the print backwards on to a wooden block and then carve a wooden printing block called a "sumihan" (black ink block). The preliminary design and aratame-in were both carved onto the sumihan together. Once the carving is complete, several copies of a black print called "sumi-zuri" (monochrome black and white print) or kyogo-zuri (proof impression) (bottom left figure) are printed and delivered to a painter. (Figure 4) The painter at this point then specifies the colors and the engraver then carves the color blocks based on the painter's specifications. (Figure 5) The sumihan and irohan (color block) are delivered to a printer, the painter then looks at the first prints informs the engraver of any carving mistakes and gives the printer instructions on coloring and graded color-printing. A single work is finally completed in this manner. The finished nishiki-e is sold by the publisher in their own storefront or were sold wholesale to retail specialist e-zoshi-ya and then resold in amusement districts and other locations. (Figure 7)

Toto Shiba Atagoyama Enbo Shinagawa Kaizu ![]() /

/

by Shotei Hokuju, printed by Yamamoto

<Call no. : 寄別1-8-1-4>]

It is commonly believed initial print runs consisted of 200 copies, with more copies being printed if the existing prints sell out. In general, a single printing block could be used for print 1,000 to 1,500 prints, or even up to 2,000 prints for prints that sold well. It is said that for the popular Fifty-three Stations of Tokaido by Utagawa Hiroshige, over 10,000 prints were made. In the Ukiyo-e No Kansho Kiso Chishiki (Basic knowledge for appreciating ukiyo-e) Adachi Isamu of the Adachi Institute of Woodcut Prints hypothesizes that the Gaifu Kaisei (Red Mt. Fuji) by Katsushika Hokusai may have been the most printed ukiyo-e (pictures of the floating world) as the wood block was used so much that the edgelines of the mountains in the picture were worn away.

The price of an average nishiki-e is said to have been about the cost of one bowl of soba buckwheat. The 1859 journal of Yamamoto Joken, a Confucian scholar of the Yoshida Clan, states that 1 print cost 24 mon (an obsolete unit of currency) which at current monetary value would be a few hundred yen. Some works were also higher cost, such as works by popular artists, works with a large number of colors, and works with superior quality carving or printing.

In Shikitei Sanba's Ukiyo Buro novel, there is a scene where children are exchanging yakusha-e (actor print) and critiquing their quality in the changing room of a bathhouse. (Relevant section![]() ) In addition, it is also noted in the Enyu Nikki journal of Yanagisawa Nobutoki, head of the Koriyama Clan, that booksellers would deliver kusazoshi (woodblock print literature) and nishiki-e to residences and that when Nobutoki visited Edo City proper, he often bought works as souvenirs. This shows that nishiki-e were popular with a variety of people from Daimyo (feudal lords) to children.

) In addition, it is also noted in the Enyu Nikki journal of Yanagisawa Nobutoki, head of the Koriyama Clan, that booksellers would deliver kusazoshi (woodblock print literature) and nishiki-e to residences and that when Nobutoki visited Edo City proper, he often bought works as souvenirs. This shows that nishiki-e were popular with a variety of people from Daimyo (feudal lords) to children.

Imayo Mitate Shinokosho ![]() by Toyokuni, printed by Iwaki in 1857 <Call no. : 寄別2-8-1-1>

by Toyokuni, printed by Iwaki in 1857 <Call no. : 寄別2-8-1-1>

Yakusha-e and landscape pictures are on display in the storefront of a nishiki-e shop,

with an advertisement for the One Hundred Famous Views of Edo visible at the left edge.

Bibliography

- Kobayashi Tadashi and Okubo Jun'ichi, Ukiyo-e no kansho kiso chishiki, Shibundo, 1994 <Call no. : KC172-E56>

- Okubo Jun'ichi , Ukiyo-e Coler ed, Iwanami shoten, 2008 <Call no. : KC172-J22>

- Takahashi Katsuhiko, Ukiyo-e kansho jiten, Kodansha, 1987 <Call no. : KC172-97>