Chapter 2 Signatures (1)

Signatures indicate many different things. They can represent approval or stand as proof of authorship or ownership. Here is a collection of a variety of signatures from commemorative messages, dedications of deluxe editions, autograph collections, official documents, and portrait photography.

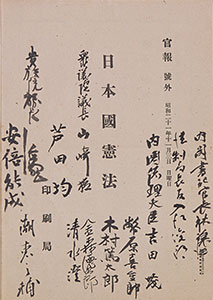

109 Nihonkoku Kempo (Kampo Gogai)[Irie Toshio Papers: 46]

This is a Special Edition of the Official Gazette, in which the Constitution of Japan was promulgated on November 3, 1946. It is presumed that IRIE Toshio, who was Director-General of the Bureau of Legislation at the time, collected these signatures of important people to commemorate promulgation of the Constitution.

People who signed and their position at the time

- YOSHIDA Shigeru, Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs

- KANAMORI Tokujiro, Minister of State (in charge of Constitution)*, later, First Librarian of the National Diet Library

- ASHIDA Hitoshi, Chairman of the Committee on the Bill for Revision of the Imperial Constitution in the House of Representatives

- IRIE Toshio, Director General of the Bureau of Legislation

- SHIDEHARA Kijuro, Minister of State and President of Demobilization Agency as well as former Prime Minister

- HAYASHI Joji, Chief Secretary of the Cabinet

- KIMURA Tokutaro, Minister of Justice

- ABE Yoshishige, Chairman of the House of Peer’s Special Committee on Revision of the Imperial Constitution

- YAMAZAKI Takeshi, Speaker of the House of Representatives

- TOKUGAWA Iemasa, President of the House of Peers

- SHIMIZU Toru, President of the Privy Council

- USHIO Shigenosuke, Vice-chairman of the Privy Council

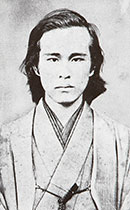

UEKI Emori, 1857-1892

A thinker and politician. Influenced by Itagaki Taisuke, he participated in the Risshisha, revived the Aikokusha, and the League for Establishing a National Assembly. Standing against the autocratic rule of the Meiji Government, he led the Freedom and People's Rights Movement and expressed his ideas through the Dai-Nippon National Constitution Proposal, private draft constitutions, and other activities. His main work includes Minken jiyuron, Tempu jinkenben, and Ikkyoku giinron.

A thinker and politician. Influenced by Itagaki Taisuke, he participated in the Risshisha, revived the Aikokusha, and the League for Establishing a National Assembly. Standing against the autocratic rule of the Meiji Government, he led the Freedom and People's Rights Movement and expressed his ideas through the Dai-Nippon National Constitution Proposal, private draft constitutions, and other activities. His main work includes Minken jiyuron, Tempu jinkenben, and Ikkyoku giinron.

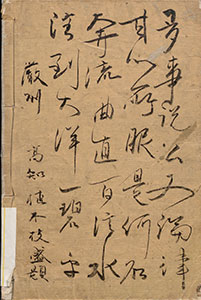

110 ITAGAKI Taisuke, GOKO Shuji (ed.), Itagaki seihoron, Jiyuro, 1881[特39-254]

This anthology of discourse was originally serialized in the Aikoku shirin (later re-titled as Aikoku shinshi) magazine, which was first published in March 1880 by Ueki Emori, and later published in this collection by Goko Shuji. The poem was written by Ueki in his own hand on the back cover.

The discourse itself is presented as a transcription of Itagaki’s speech by Ueki, although it is uncertain whether or not Itagaki himself developed the ideas presented, and there are those argue that this is Ueki’s own work.

SHIMMURA Izuru, 1876-1967

One of the leading Japanese linguists from the Meiji to the Showa eras, he is also well known as an editor of the Kojien dictionary. His studies of the Japanese language history centered on phonology and language families, and he also made contributions in a wide variety of subjects, including the study of Namban language and culture, and was well regarded as an essayist. Of particular note was his study of the etymology and history of the Japanese language, which he pioneered by introducing comparative-linguistics methods from Europe.

One of the leading Japanese linguists from the Meiji to the Showa eras, he is also well known as an editor of the Kojien dictionary. His studies of the Japanese language history centered on phonology and language families, and he also made contributions in a wide variety of subjects, including the study of Namban language and culture, and was well regarded as an essayist. Of particular note was his study of the etymology and history of the Japanese language, which he pioneered by introducing comparative-linguistics methods from Europe.

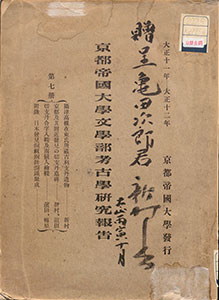

111 Kyoto Teikoku Daigaku Bungakubu Kokogaku Kenkyushitsu (ed.), Kyoto teikoku daigaku bungakubu kokogaku kenkyu hokoku, Vol. 7, Kyoto Teikoku Daigaku, 1923[14.5-3]* (The inserted material is [202.5-Ky995k].)

This report was presented by Shimmura Izuru to Japanese linguist Kameda Jiro and has an autograph dedication from Shimmura on its cover.

Shimmura took a position as professor at the Imperial University of Kyoto in 1909 and was in charge of the linguistics course until retirement. This book contains the results of his extensive research into Namban culture and was dedicated to Kameda, who had been a close colleague for quite some time. In fact, in his own studies, Shimmura often referred both to Kameda’s work and personal library. Known as the Kameda Collection, it is currently owned by the National Diet Library. The inserted material is a book from the Kameda Collection.

TAKAMURA Kotaro, 1883–1956

Kotaro was the eldest son of sculptor Takamura Koun as well as poet and a sculptor in his own right. His love of literature led him to join the Shinshisha led by Yosano Tekkan while studying sculpture at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts. After studying in Europe and the Americas, he translated Auguste Rodin’s works into Japanese and wrote many critiques on art. His poetry contributed to the establishment of colloquial free verse as a legitimate style of Japanese poetry. His notable works include the collections of poetry Dotei and Chieko sho (Chieko's Sky) and the sculptures Te (lit. Hand) and Otome no zo.

Kotaro was the eldest son of sculptor Takamura Koun as well as poet and a sculptor in his own right. His love of literature led him to join the Shinshisha led by Yosano Tekkan while studying sculpture at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts. After studying in Europe and the Americas, he translated Auguste Rodin’s works into Japanese and wrote many critiques on art. His poetry contributed to the establishment of colloquial free verse as a legitimate style of Japanese poetry. His notable works include the collections of poetry Dotei and Chieko sho (Chieko's Sky) and the sculptures Te (lit. Hand) and Otome no zo.

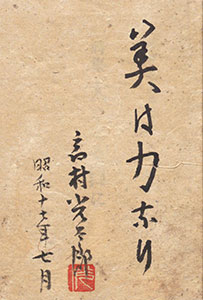

112 Oinaru hi ni, Dotosha, 1942[KH577-J1]

This anthology was his first collection of poetry and featured poems on the subject of war. The sentence “Bi wa chikara nari (Beauty is power)” is written on the flyleaf in the author’s own hand. He often used this phrase when giving autographs both during and after the war. The phrase was a direct expression of his extraordinary resolution during the most difficult times of his life, particularly while grieving over the loss of his beloved wife, Chieko. During the war, he published a large number of poems in support of the war effort and encouraged people to keep their hope up through the power of beauty, but in his later works reflected on personal responsibility.

HORIGUCHI Daigaku, 1892-1981

A poet and translator. His most notable anthologies of poetry are Gekko to piero and Suna no makura. He translated a number of novels and stage plays from French into Japanese while breathing fresh life into contemporary Japanese poetry through an anthology of contemporary French poetry translated into Japanese, entitled Gekka no ichigun. His ability to incorporate neologisms into elegant Japanese expressions, thereby conveying accurately a sense of the French language, had a great influence on Yokomitsu Riichi, Kawabata Yasunari, and a young Mishima Yukio.

A poet and translator. His most notable anthologies of poetry are Gekko to piero and Suna no makura. He translated a number of novels and stage plays from French into Japanese while breathing fresh life into contemporary Japanese poetry through an anthology of contemporary French poetry translated into Japanese, entitled Gekka no ichigun. His ability to incorporate neologisms into elegant Japanese expressions, thereby conveying accurately a sense of the French language, had a great influence on Yokomitsu Riichi, Kawabata Yasunari, and a young Mishima Yukio.

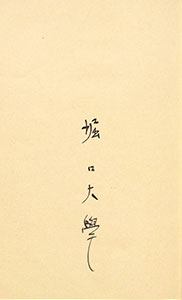

113 Arthur Rimbaud, Yoidorebune, Shintensha, 1936[新別よ-1]

A translation by Horiguchi Daigaku of the long poem Le Bateau ivre (1871) by the 19th-century French Impressionist poet Arthur Rimbaud. Le Bateau ivre, a work created before Rimbaud turned 17 years old, is said to be one of his finest rhymed verses.

Although Horiguchi had previously translated works by other French poets, including Paul-Marie Verlaine and Jean Cocteau, he described this work as a “sparkling diamond of a poem by a young-boy poet, that was far beyond my own abilities” (Rambo shishu, 1949). Having struggled to translate this poem, Horiguchi did not attempt to translate another work by Rimbaud for more than a decade. The inserted material is a special edition of only 250 copies. Horiguchi’s signature is on the flyleaf.

TACHIHARA Michizo, 1914-1939

A poet and architect. Tachihara became familiar with tanka and other forms of poetry during his youth. His prodigious talent expressed itself through architecture, poetry, and painting. He died at the age of 26, not long after receiving the 1st Nakahara Chuya Award. He is remembered as one of Japan’s best lyric poets.

A poet and architect. Tachihara became familiar with tanka and other forms of poetry during his youth. His prodigious talent expressed itself through architecture, poetry, and painting. He died at the age of 26, not long after receiving the 1st Nakahara Chuya Award. He is remembered as one of Japan’s best lyric poets.

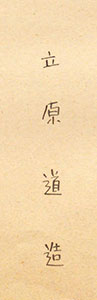

114 Akatsuki to yube no shi, Fushinshi Shisha, 1937[KH597-H5]

One of two anthologies of Tachihara’s poetry that he selected himself. He published this work at his own expense following Wasuregusa ni yosu in the same year. His signature appears on the reverse of the title page.

The design is modeled on musical scores, which represents Tachihara’s intent to “create poetry in the form of music”. This is essentially a limited-edition of 165 copies, published privately for Tachihara’s personal use. There are 10 sonnets, comprising 14 lines of rhymed verse on various subjects. Fushinshi (hyacinth) was Tachihara’s favorite flower and formed part of the name of the publishing company that he established: Fushinshi Shisha. A plaque displaying this name hung on the third floor of his home.

115 TOKUTOMI Iichiro, Tanjobi, 2nd ed., Min'yusha, 1892[159.8-To454t]

An autograph book. It is a memorandum of birthdays with the date accompanied by a proverb or Chinese poem selected by Tokutomi Soho (a.k.a. Iichiro) on one side and entries made on the facing page. Family and friends filled in their names on their birthdays. There are also illustrations drawn by Kubota Beisen, a painter who was a close friend of Soho.

The inserted material is from the library of Japanese scholar Kameda Jiro’s collection, which is indicative of the close friendship between the two men.

In the preface to Tanjosetsu, Soho emphasizes the importance of celebrating the changing of the seasons (Shukusetsu), particularly during times when the world was changing so rapidly. Until 1949, the traditional manner of counting one’s age in Japan was to add a year at the New Year, and there was no celebration of individual birthdays. This work is thought to have come after Tansetsuseisho, a book published in the UK in 1866 that was both a Bible and a birthday autograph book.