Column

Gutenberg, Man of Mystery

Though not everybody agrees, today it is widely said that Johann Gutenberg (c.1400-1468), a native of Mainz, Germany, was the inventor of typographic printing.

Except for the court documents described later, the oldest historical record in which the name Gutenberg is referred to as a printer concerns an event mentioned in several manuscripts that remain in France. According to these manuscripts, Charles VII, King of France, issued a decree on October 4, 1458 to dispatch Nicolaus Jenson to Mainz to learn the art of typographic printing invented by Gutenberg. However, the original copy of this decree is not extant, and one of these manuscripts, Ms. fr. 5524, which is owned by the National Library of France (Bibliothèque nationale de France), was produced between 1559 and 1560. There is no record of Jenson's activities in Mainz, but later, in 1470, he started printing using beautiful Roman type, not in Paris but in Venice, and produced nearly 100 titles of incunabula over the next ten years. In Paris, three Germans (U. Gering, M. Crantz, and M. Friburger) started up a printing business in 1470, the same year as Jenson.

The second oldest document in which Gutenberg's name is referred to is the poem included at the end of Justinian's Institutiones, which was printed by Peter Schöffer (d.1502) in Mainz in 1468. In the poem reference is made to two Johanns, both natives of Mainz, skilled at carving letters and becoming the first printers. One of the two Johanns is Johann Fust (d.1466), and the other is Johann Gutenberg. The two men launched a joint printing business financed by Fust, but they were involved in a legal dispute in 1455 over the repayment of loans, and a document called the "Helmasperger Notarial Instrument," which describes the proceedings of the trial, was discovered in 1734. This instrument refers to "solte," "permet, papier, dinte" (apparatus, parchment, paper, ink) clearly indicating that the trial concerned investments in printing. The verdict went against Gutenberg, who was ordered to surrender all printing equipment to his partner. The printing house was later passed on by Fust to his son-in-law Schöffer, who had acquired printing techniques as one of Gutenberg's apprentices. Schöffer produced more than 200 titles of incunabula.

In the meantime, Gutenberg continued printing at another workshop even after the trial, and it is believed that he printed the 31-line Indulgence, Türken-Kalender, Catholicon and other books and documents. In actuality, however, his name is not printed in any of these books or documents as in the 42-line Bible. It is mentioned in the colophon of Catholicon, a monumental work of 373 folio leaves, that the book was printed in the glorious city of Mainz in 1460 using not a pen but a harmonious marriage of punch and matrix. Since the colophon is full of words of pride expressed by the inventor of printing, the book had been attributed to Gutenberg. Recent studies, however, have confirmed three versions of Catholicon, with some reports claiming that some copies were printed in 1469 and others around 1472 while other reports saying that they were all printed in 1469. At present many researchers have agreed that Catholicon was not printed by Gutenberg.

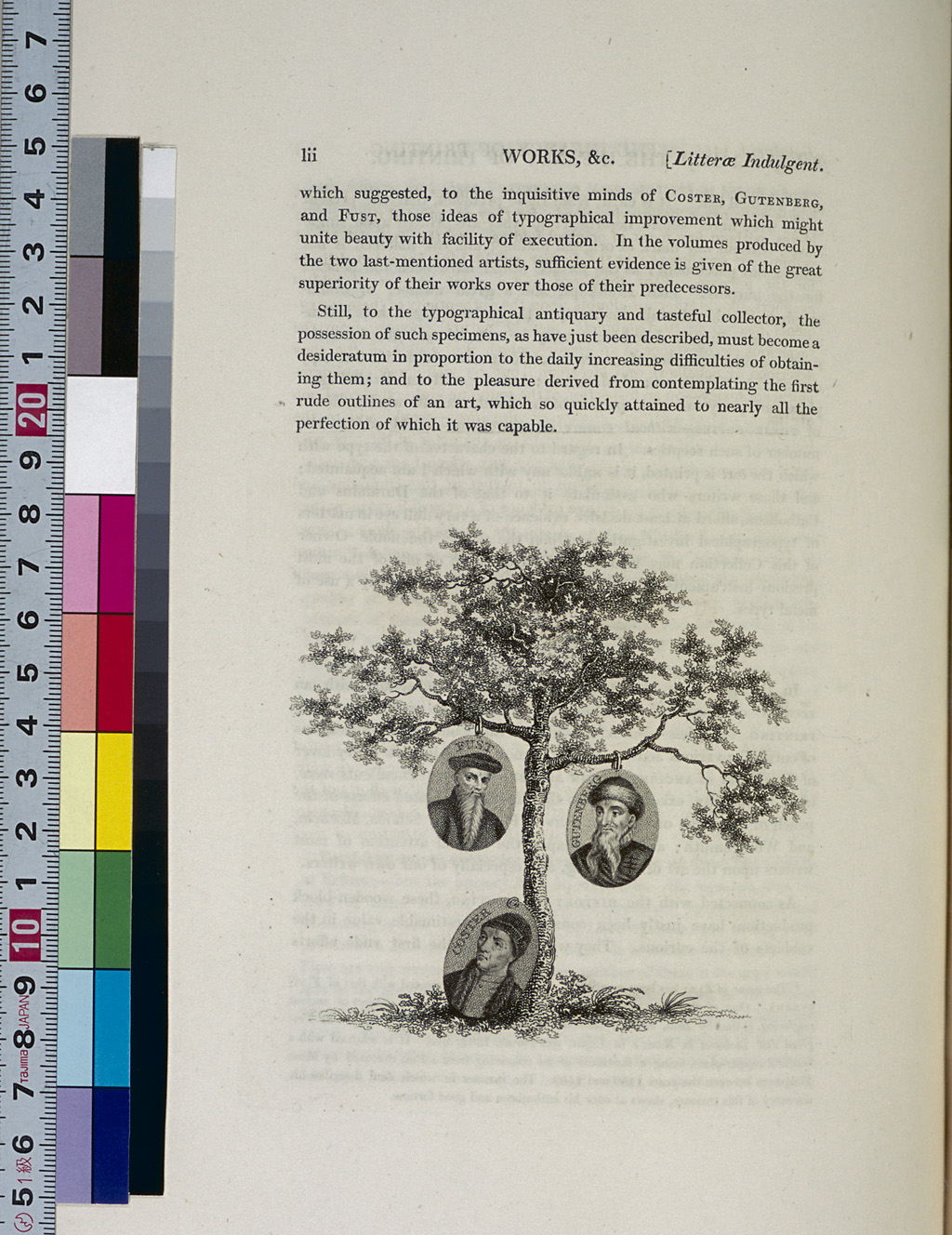

Further details on Gutenberg are not known, and therefore, since early on, there have been arguments as to who the true inventor of printing is. H. Junius's Batavia, published in 1588, states that the art of printing was invented by Laurens Coster of Haarlem and that Johann Fust ran off with this invention. There is, however, no objective evidence that Coster is the true inventor of printing. In 1765, G. Meerman (1722-71) published his theory that Coster invented wooden type printing between 1430 and 1440, and this invention developed into metal type printing. Later, various studies were conducted about the mutual effects and relationships between wood block printing and metal type printing techniques as well as about when the primitive printed materials called "Costeriana" were produced. Costeriana include materials such as Spiegel der menselijker behoudenisse and Donatus's Ars minor, and many examples of Costeriana are found in the Netherlands. In his studies published in 1870, Antonius van der Linde, a Dutch scholar, argued that all the men of that period named Coster had been engaged in other occupations, but not in printing. It has also been made clear that Costeriana were produced during the period from 1463 to 1480. Based on these findings, many researchers now believe that Gutenberg is the most probable inventor of printing.

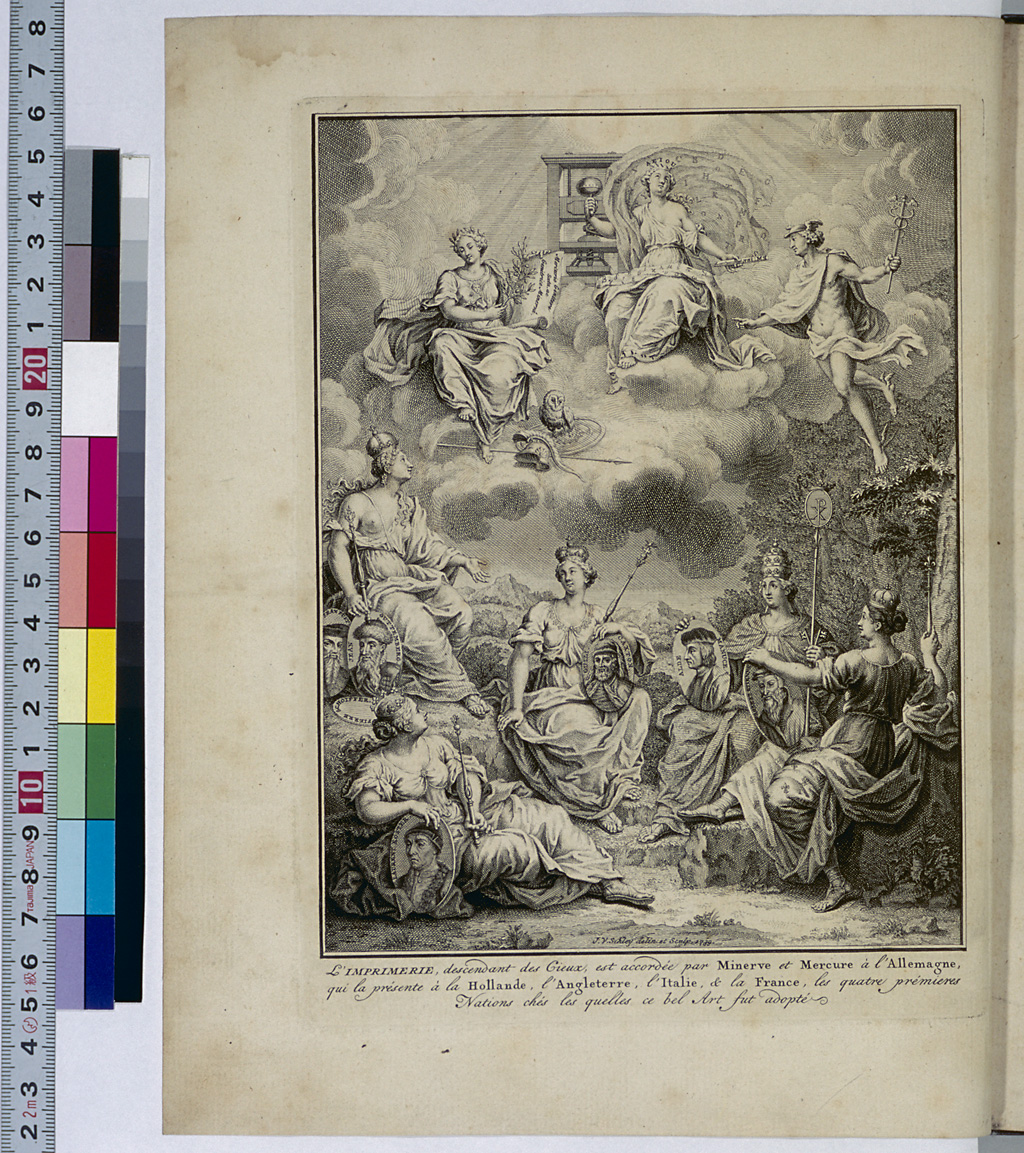

In fact, details of early printers are not well known. During the decade after Gutenberg printed the 42-line Bible, besides Fust and Schöffer as mentioned earlier, there were only five men in four cities known to have been active in the printing business, including Albrecht Pfister of Bamberg. During the subsequent five-year period from 1466 to 1470, however, printing began in ten other cities, and it is now confirmed that another 27 printers started printing. It seems that these printers acquired their printing techniques from Gutenberg and then scattered throughout Europe, but details of how the art of printing spread are not yet known. The art of printing, however, had a great social impact on the age in general. Many portraits of these early printers were painted in the 16th century and later. Most of these portraits are the product of the painter's imagination, and presumably this is true of the several portraits of Gutenberg. The oldest of his portraits is a woodprint produced in the second half of the 16th century, and many other portraits of the German printer appear to have been based on this woodprint. Copperplate and lithographic portraits of Gutenberg were produced for the frontispiece of books, and there are oil paintings and bronze statues of him as well.

For more information on Gutenberg, please look at the following Web site: