(2) Toward the Domestic Production (second to fourth National Industrial Exhibitions)

Second National Industrial Exhibition, 1881, Tokyo

The inflation triggered by the Seinan Civil War forced the scaling back of Japanese industrial promotion policies. Despite being held against such a background, the Second National Industrial Exhibition surpassed the previous event in scale. It seems that this partly owed to the efforts of the persons appointed in each local district to encourage participation in the event. At the event, exhibits were displayed in categories, with the emphasis on comparison between the products. Also at this event, the majority of the exhibits were displayed by the Japanese government, especially by the Kanno-kyoku (reorganized into the Nomu-kyoku of the Noshomu-sho (Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce) as of the end of the event) and by the Kobu-sho.

Approximately one third of the exhibits were related to spinning. However, excluding an improved version of the gara-bo created by Tatchi Gaun, most of the exhibits were merely imitations of the gara-bo. Since a patent system had not yet been established in those days, both the improved gara-bo and the imitations won awards. (See the Column: Patent System in the Meiji Period.) Also noteworthy were the brothers Yasushi Watanabe and Tokuzo Shibata. After winning an award for their waterwheel-operated loom at the first National Industrial Exhibition, they continued improving the machine based on the design of an American product that they obtained at the event, and gained a further award for their improved foot-operated machine at the second National Industrial Exhibition.

Following spinning machines, agricultural machines comprised the second largest group of products. Mita Agricultural Tool Factory of the Kanno-kyoku (Agricultural Bureau) won awards for their rice hullers and pumps, although they were all merely imitations of foreign products. Machinery for large farms in foreign countries was not appropriate for use in Japan without some adjustments. In this regard, subsequent development of agricultural machinery in Japan was promoted not by the import of foreign technologies but by the development of Japanese indigenous technologies.

In the category of prime movers, the number of exhibits by the private sector was increased, providing an early sign of the development of steam power use. (Actually, two years after the event, Osaka Cotton Spinning, renowned as a large spinning company using steam engines, was established.)

In terms of industrial promotion, expositions drew many exhibits from a wide variety of regions in Japan, serving as an opportunity for identifying the conditions of local industries. However, it seems that the general public had not yet recognized that such participation in expositions would lead to the generation of benefits.

Third National Industrial Exhibition, 1890, Tokyo

The third National Industrial Exhibition was held, indicating that such events had begun to establish themselves firmly in Japan. Items exhibited by the government were regarded as ineligible for prize rewards, highlighting the exhibition's characteristic as an event for promoting industries in the private sector. Since the grade of a given award had considerable influence on the commercial value of an exhibit, some exhibitors complained of the judgment result. Following the enactment of the Shohyo Jorei (trademark ordinance) in 1884, the Japanese patent system began to be established. The third National Industrial Exhibition attracted many more exhibits than the previous event, drawing a wider variety of items. In this regard, the categories of machinery products were reorganized into more detailed ones.

The number of exhibits from the private sector increased approximately four-fold from the previous event. However, all large machinery was exhibited as sample items by the government. In the category of "Balloons, Steam Trains, Steamships, etc.," which marked the largest number of exhibits of all the categories, most of the exhibits were harnesses. Neither steam vehicles nor electric railcars were exhibited. At the venue, Ichisuke Fujioka of Tokyo Electric Lamp Company operated an imported electric railcar. However, the public sector still dominated, especially in the railroad field, resulting in a lack of railroad-related exhibits. Meanwhile, the shipbuilding field had already been industrialized and privatized at its early stage. Kawasaki Shipyard exhibited a model of a vessel for transporting cannons; it was an iron steamship. Also, the Kaigun-sho (Ministry of Navy) exhibited a warship model as a sample item.

While the number of exhibits related to spinning was as large as ever, no dramatic improvements were to be found at the third National Industrial Exhibition. One of the few exhibitors who were able to win awards for their spinning machinery was Naosaburo Minorikawa, who went on to win many awards at subsequent National Industrial Exhibitions.

In the category of agricultural machinery, Mankichi Watanabe won an award for his convenient beating and winnowing machine (a threshing machine converted from a horse-drawn type to a manually operated one). Although the machine went against the aim of the Noshomu-sho (Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce), which sought to save human labor, his award reflected the actual conditions of those days, namely that human labor costs were lower than the cost of horse usage.

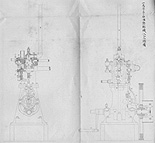

In the category of prime movers, only 17 items were exhibited. However, Tokyo Electric Lamp Company exhibited an imitation of an Edison dynamo, and other products, indicating the coming of the period of electricity. The electricity businesses based on power generation at central stations was begun by the Tokyo Electric Lamp Company (established in 1886). The company produced incandescent lamps. Subsequently, electric lamp companies were founded one after another in Osaka, Kyoto and other regions. Meanwhile, Ishikawajima Shipyard won an award for its high pressure steam machine for vessels. Thus, Japan witnessed the dawning of the private sector machine industry.

Fourth National Industrial Exhibition, 1895, Kyoto

The fourth National Industrial Exhibition witnessed a decline in the number of exhibits in all categories except for the industrial category. It is said that this decrease was partly because shipyards were very busy due to the Sino-Japanese War, and also because means of transportation were unavailable due to the requisition of transportation vessels.

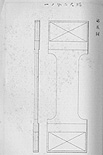

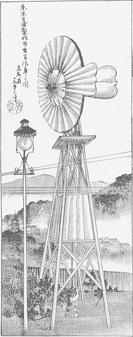

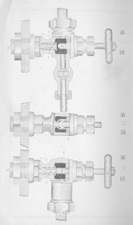

In the category of prime movers, which had always attracted wide attention, only seven items were exhibited. Awards were granted for a windmill by Shibaura Engineering Works (currently known as Toshiba Co.) and a column-type water gauge (a device for preventing boiler accidents due to increase in pressure) by Sotaro Fujii.

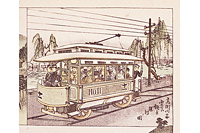

On the other hand, new industries were steadily growing, leading to the creation of a new category: "Electricity Generation and Application." Kyoto Electric Railroad, which was established in 1894, operated Japan's first commercial electric railcars in Kyoto (albeit featuring both domestic and foreign motors). In the field of electricity, there were quite a number of items for which Japan needed to depend on imports. Nevertheless, Kibataro Oki, (the founder of the forerunner of Oki Electric Industry), exhibited a telegraph and a telephone, while Shibaura Engineering Works displayed a transformer and an arc lamp. They both won awards.

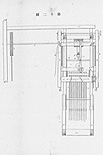

In the category of spinning-related machinery, the number of exhibits was high, although their quality was low. Highly valued in such circumstances was a silk reeling machine exhibited by Naosaburo Minorikawa. Operated at the venue, this machine (a four-roller silk reeling machine, with its number of rollers for reeling raw silk increased from two to four in a bid to raise productivity) was subsequently used across Japan.

As a matter of fact, there were no other noteworthy exhibits. The event was characterized by the participation of the founders of companies renowned today, such as Tokichi Asanuma (of Asanuma & Co., Ltd.), Rokuemon Sugiura (of Konica), and Yoshichi Yamada (of Furukawa Electric). It seems that National Industrial Exhibitions had begun to be regarded as opportunities to promote products, inviting participation from the private sector.

Exhibits of the fourth National Industrial Exhibition

Section 7, Machinery Exhibits

| Category | Machinery | No. of Exhibits | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| 46 | Prime Movers | 7 | 2 |

| 47 | Power Transmission Machines | 78 | 1 |

| 48 | Processing | 24 | - |

| 49 | Manufacturing | 171 | 7 |

| 50 | Transportation | 60 | - |

| 51 | Pumping and Ventilation | 8 | - |

| 52 | Fire Fighting | 11 | - |

| 53 | Agriculture | 5 | - |

| 54 | Mining and Metallurgy | 0 | - |

| 55 | Civil Engineering and Construction | 0 | - |

| 56 | Electricity Generation and Application | 131 | - |

| 57 | Measurement and Testing | 2 | - |

| Total | 497 | 10 |

|

| Sample Items Exhibited by Government Agencies | - | 1 |

|

- Source:

Dai yonkai nijuhachinen naikoku kangyo hakurankai shinsa hokoku(Dai yonkai naikoku kangyo hakurankai jimukyoku, 1896)